Our son Michael got his name from Carolyn’s great-grandfather Michael Patrick Donlin. No, this wasn’t the “Turkey” Mike Donlin who starred for the New York Giants. Our Mike Donlin lived in Ireland during the Great Famine. He spent his youth scaling sea cliffs, stealing eggs from sea gulls to fight off starvation. We don’t have any reason to believe that he played baseball, but that’s okay. Our son Michael is more than willing to compensate for that family shortcoming. Trouble is, he’s had some trouble getting recognition. He’s not a big kid, and his dad doesn’t have connections. After spending last spring watching his coaches ignore him, I wasn’t sure I wanted to put up with another year of Pony League. We signed him up for a couple dance classes. We would have had him play soccer in the fall, but baseball was cheaper, and I’m a sucker for cheaper, so we signed him up for fall baseball.

My Dad was a San Francisco Giants fanatic. His unfailing allegiance to the Giants began with his childhood, when he and the Giants were in New York. Listening to him talk about Willie Mays, you’d have thought Mays parted the Red Sea. Dad could never shake his addiction to the Giants no matter how badly the Giants did. He knew it to be a waste of time, but the Giants were too much a part of him to be cast aside. He endured year after year of mediocre seasons. To be sure, there were some good Giants teams over those decades, but the best of them hadn’t won the big prize since New York, back in ’54.

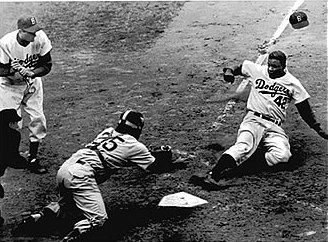

Last year, the Giants won their division on the last day of the regular season. As they battled through the playoffs, Michael was playing “fall ball,” watching the Giants make history and ratcheting up the intensity of his own play, diving or sliding head-first whenever he got a chance. He did well enough to earn the team “most valuable player” honor, and his fall ball coach expressed disappointment next spring when he failed to acquire Michael in the draft.

The Giants finally won the World Series. Obviously, this was big news in our family. It made me very happy to know that Dad—who’d just turned 86 years old—had finally seen the SF Giants win it all. Being blind, he had to see it with his ears, but he saw it just the same.

Last April, the day before we had planned to go on a trip to the desert, we got news that Dad had suffered a heart attack, and that he would not be long for the world. We changed our vacation plans, and, immediately after Michael’s game the next morning, we hit the highway for Oregon. Every time we stopped, whether to camp, to fill up the gas tank, to eat, or to walk the dog, Michael wanted to play catch. He had thoughts for his grandfather, however, and he was worried that the hospital might not let him into his grandfather’s room. Well, it turned out that he would be permitted to meet his grandfather a couple times. The second time, Michael wore his baseball glove, and presented it as though it were his hand. Grandpa’s frail fingers inspected the glove. Perhaps just making conversation—or perhaps not, Dad asked Michael to play for him. I thought nothing of it at the time.

After several days of visiting, we sped back home to San Jose and, prodded on by Michael, got back just in time to get him to his baseball practice. His team was preparing to face the Giants, the team at the top of the league. On the morning before that big game, we received word that Dad had passed away, and Carolyn dutifully informed Michael just before game time. His response was “Why’d you have to tell me now?!” Carolyn, desperate to recover from that mistake, then remembered Grandpa’s request, and she reminded Michael. Suddenly he didn’t mind so much. He would play this game for Grandpa, ironically, against the “Giants.”

It didn’t start well. Michael grounded out, then he struck out. Carolyn went to the dugout to check on him. He was crying. I didn’t try to comfort him. I didn’t know how to begin. But his team—the Astros—managed to build up a 2-0 lead against the Giants, and in the final inning, the Astros’ manager called Michael in to take the mound and finish the game. This was a first. Michael had been telling me that he could be a closer like the Astros’ ace “Lights-out” Ledbetter. Michael didn’t pitch flawlessly that day, but he was effective—as usual. He even dropped to the ground to nab a soft line drive just before it would have hit the pitcher’s mound and bounced who-knows-where. Michael completed the shutout of those looming Giants, and was honored with the game ball.

What a way to see Grandpa off.

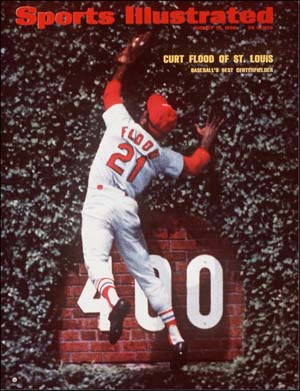

The Astros finished the regular season in first place. That victory against the Giants, as things turned out, served as the tie-breaker. Michael has three of the best players in the league as teammates, but he too has played a big part in the Astros’ success. During the regular season, Michael was 3rd on the team in run production, 4th in batting, and 3rd in extra base hits (and all without a composite bat). As one of the team’s four regular pitchers, he had the second best ERA, allowing only three earned runs all season. But more impressive, this kid loves the game. He is so full of baseball it can get a little embarrassing. Last night after practice, he received his jersey for an upcoming tournament. He’d asked for number 24, Willie Mays’ number, and he got it. He didn’t make the slightest effort to hide his joy. It was as though he thought he’d been transformed by that jersey into the Say Hey Kid himself. I was a little overwhelmed, and I barked at him to get his bat and helmet, but inside I was happy for him; I was jumping with joy.