Recent news in the Baha’i world of “mass teaching” efforts remind me of one of my favorite songs from childhood. It was a Baha’i-ified traditional C-major tune with an occasional descending B-flat for blues effect, probably a Negro spiritual, that I knew as “We Are Soldiers in God’s Army”. I’ve been teaching myself to play it on violin lately, and have felt compelled to some liberty with the lyrics.

The Baha’i lyrics are best described as millenarian, Biblical, and didactic; in general, a call to convert the masses. They begin as follows:

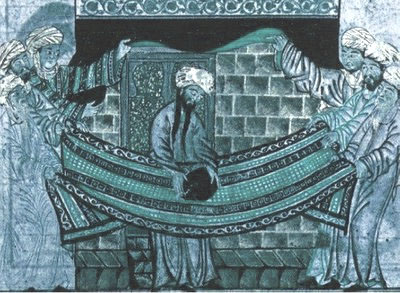

Now the Báb blew His trumpet

Announcing to the world the time had come

And like a thief in the night, He came by the Gate

And said He was the Promised One

Verse after verse, the song parades Baha’i leaders before us, exhorting Baha’is to get out and proselytize in the footsteps of their leaders:

Bahá’u’lláh was the Prophet

He had the Word that is right for now

And when the road got rough and the going got tough

He just stood there and taught anyhow

These verses refrain a curious conflict of tenses (perfect vs. imperfect) that brings to mind some of the intrinsic problems with universal progressive revelation, such as “if it was right for now 150 years ago, is it right for the present “now”? And, “is it really right for everybody?

The chorus goes as follows:

We are soldiers in God’s army

We gotta stop and teach the Word for now

We gotta hold a lotta love and unity

We gotta hold it up until we die

I don’t have much of a problem with the verses, as they tend to say so much about the predominant Baha’i state of mind, and truly, the chorus does as well, but I think some variations on the chorus might do the song some good. For example:

(Oh-oh-oh-owoh-oh …)

We are minions of the Millennium

We gotta stop–and think for ourselves

It’s time to see (its time to see beyond our idol called “Unity”)

It’s time to break it down so we can see.

Here the singer turns from the mic and says “break it down”, whereupon the maestro steps into his A-major improvisation.

Post-solo:

We are minions of the Millennium

We gotta stop–and “see with our own eyes”

We gotta think instead of followin’ the leader

There’s more to life than playin’ “Simon says”

And finally, as the music fades:

We are minions of the Millennium

We’ve had our fun–playin’ blind man’s bluff

We gotta think (we gotta think instead of followin’ the leader)

We gotta use our eyes so we can see.