Since Iran deteriorated into Islamic fundamentalism in 1979, and the Ayatollahs resurfaced to rid Iran of unclean things such as infidels, heretics, and homosexuals, we haven’t heard much from the starry-eyed orientalist; that scholar who tires of the daunting empiricism, formal scientific process, excessive prosperity, and agnostic materialism of the West, and turns to the Orient of whirling dervishes and flying carpets for a renovation of romance.

It’s rather like stepping back in time.

I can understand the need, but I cannot bear to conflate a feline curiosity for the exotic with the transparently negative escapism of these naive daydreamers.

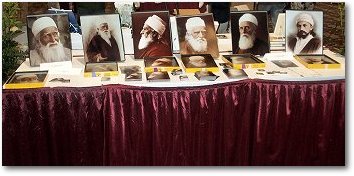

The last of these gullible scholastic tourists was perhaps Henry Corbin, who died in his native France in October 1978, while Ruhollah Khomeini was living in exile in the very same land. I recently read Corbin’s book Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth (1960), hoping to educate myself further on the thought and culture of ancient Iran.

One of the dominant themes of the book is its continual denigration of the West and its loss of faith. Complementing that theme is the book’s air of absolute certainty with regard to the author’s own gnostic and theosophical doctrines. Fair enough: it would do Corbin no good to appear uncertain or impartial, for it is clearly just that impartiality and “pious agnosticism” of the West that he yearns to forsake.

Corbin’s primary need, next to a general desire to believe and to be a Persian, appears to be to find a foundation for immortality. He finds his beloved eternity in a sort of a world of forms—or images, or more: it’s a world of dimensions, sights, smells, and tastes just like our own—very real. The only difference is that his world of images has no death or deterioration.

Let me guess what you’re thinking: in a world full of unchanging, immortal images, can anything or anyone ever be truly alive?

To each his own. Some people simply cannot see the forest for the trees. They cannot see that a living world exists right before their eyes. All they need do to attain immortality is to loosen their grasp on their idols and let the changes flow. But they refuse to acknowledge the rules of the game, though it be the only game in town.

“Through my meeting with Suhrawardi, my spiritual destiny for the passage through this world was sealed.”

—Henry Corbin, Jambet, 1981, pp. 62-3

Corbin, purportedly following the lead of his idol, the Islamic mystic Suhrawardi, made a fundamental misjudgment of the character of Zoroastrian thought. There appears to be a consensus among scholars of Zoroastrianism that it is a life-affirming religion of this world. It is, in fact, quite the opposite of Suhrawardi’s mysticism. Suhrawardi may have revived a form of ancient thought—Manichean thought perhaps, but his efforts only served to increase the distance between Islamic and Zoroastrian Iran.

I would venture to claim that mainstream Shi’ism is closer to Zoroastrianism than the abstract, world-denying asceticism of Suhrawardi (and Sufism in general). This may possibly discredit Zoroastrianism in the eyes of Western admirers of Sufism, but it remains a fact—for better or for worse—that Zoroastrianism is not a mystical, ascetic religion. It is a religion of community and engagement with the world; in no danger of the solipsism and amoral disengagement that Sufi practitioners have always been hazardously near. Not to discredit Sufism: it offers a lot to admire, but it has little in common with the religion of pre-Islamic Iran.

Now’s it’s peculiar, though not surprising, that Corbin has ample indignation reserved for the religion of most Muslims. Attempting to distance his thinking from the suffocating legalism and orthodoxy of the dominant institutions of Islam, Corbin continually refrains the abyss between “legalistic Islam” and what he calls “spiritual Islam.”

“spiritual Islam, to be sure, … is profoundly different from the legalistic Islam, the official religion of the majority.” —page 52

The majority of Muslims, of course, lack the capacity to appreciate spiritual Islam:

“he who does not possess the inner ear cannot be made to hear …” —page 54

This kind of elitist end-run around reason leads one to wonder whether the rest of us ought to simply take his word for all his gnostic, theosophical mumbo jumbo.

One of the first tasks of this “spiritual Islam” is—of course—to recast the Qur‘an as a spiritual book:

“the ta‘wíl is preeminently the hermeneutics of symbols, the ex-egesis, the bringing out of hidden spiritual meaning.” —page 53

Corbin goes on to assert that it was by means of this methodology that Shí‘a mystics transfigured “the meaning of Islam.”

“In the Qur‘an there are verses whose complete meaning cannot be understood except by means of the spiritual hermeneutic, the Shi’ite ta‘wíl. —page 66

I suppose it would charitable of the Shí‘a to let the Sunni use their ta‘wíl, just so they can understand their own scripture? Of course, that will only benefit those with an inner ear, but it’s worth a shot.