Nietzsche’s choice of the Iranian (not necessarily Persian) prophet Zarathustra was far from arbitrary, and Nietzsche wanted us to know this.

“I have not been asked, as I should have been asked, what the name of Zarathustra means in precisely my mouth, …” — Ecce Homo

Though taking the title “the first immoralist,” Nietzsche did not suggest that his Zarathustra is the anti-Zarathustra, as one might superficially presume. Nietzsche, rather, believed that the great dualist of old would be the first man to discover “the death of God,” as it were, because of the nature of the Zarathustrian worldview.

|

|

“Zarathustra was the first to see in the struggle between good and evil the actual wheel in the working of things: the translation of morality into the realm of metaphysics, as force, cause, and end-in-itself, in his work.” — Ecce Homo

It was the cosmic dualism of Zarathustra, as Nietzsche knew the prophet, that led Nietzsche to make such use of him. To Nietzsche, as to many others, Zarathustra is the prophet that brought morality and metaphysics together, seeing good and evil as the very metaphysical fabric of reality. This was the first essential aspect of Zarathustra. The second essential aspect is the fundamental distinction between Zarathustra’s good and evil: Truth (Asha) and the Lie (Druj). To Nietzsche, Zarathustra was the most honest prophet, so Nietzsche thought that the honesty of Zarathustra would ultimately prevail over his moralism, taking him “beyond good and evil.”

“Not only has he had longer and greater experience here than any other thinker … what is more truthful than any other thinker. His teaching, and his alone, upholds truthfulness as the supremem virtue. … To tell the truth and to shoot well with arrows: that is Persian virtue. — Have I been understood?” — Ecce Homo

That triumph of honesty over the idols of moralism is a central theme of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

“I count nothing more valuable and rare today than honesty.” — TSZ, Of the Higher Man (4.13.8)

Nietzsche plays with other Zoroastrian themes throughout the book:

- Mountains: Zarathustra was as much a mountain prophet as any, and Nietzsche loved mountains.

- He returns repeatedly to purity, even speaking of the need for cleansing after childbirth.

- He honors cattle, and the ox, more than once.

- He likens Zarathustra to a rooster, a bird that is treated with reverence by Zoroastrians because of its role as a harbinger of the dawn (3.13.1).

- Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, like the Zarathustra of tradition, experiences an enlightened moment wherein he doesn’t cast a shadow.

Beyond Good & Evil

Nietzsche’s Zarathustra is no nihilist, but rather quite the opposite. The lesson is not that good and evil are irrelevant; they are crucial:

“No greater power has Zarathustra found on earth than good and evil. … without evaluation the nut of existence would be hollow.” — TSZ 1.15: Of the Thousand and One Goals

This is not the only passage where Zarathustra associates good and evil with power.

What Nietzsche’s Zarathustra discovers is that they are not static:

“Allegories are all names of good and evil: they do not express, they merely hint. A fool is he who wants knowledge of them!” — TSZ 1.22.1

“May your virtue be too lofty for the familiarity of names: and if you must talk about her, be not ashamed to stammer about her. So speak and stammer: … I do not will it as the law of a God, …” — TSZ 1.5: On Enjoying and Suffering the Passions

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus, a Greek subject of the Persian Empire who lived circa 500 B.C.E., said something quite similar about the allegorical nature of truth:

The lord whose oracle is at Delphi neither reveals nor conceals, but gives a sign.

What Zarathustra sees in good and evil is what Heraclitus sees in his Logos: a harmonious war of loving antagonists.

“… the secret of all life! That there is battle and inequality and war for power and predominance even in beauty … How divinely vault and arch here oppose one another in the struggle: how they strive against one another with light and shadow, these divinely-striving things.” — TSZ 2.7: Of The Tarantulas

How closely this observation resembles what Heraclitus sees in the bow and the lyre:

“People do not understand how that which is at variance with itself agrees with itself. There is a harmony in the bending back, as in the cases of the bow and the lyre.”

For Heraclitus, the world is not merely flux, but more: the world is a war of opposites, but it is also a symphony.

We must recognize that war is common and strife is justice, and all things happen according to strife and necessity. (DK22B80)

War is the father of all and king of all, who manifested some as gods and some as men, who made some slaves and some freemen. (DK22B53)

Heraclitus criticizes the poet who said, ‘would that strife might perish from among gods and men’ [Homer Iliad 18.107]’ for there would not be harmony without high and low notes, nor living things without female and male, which are opposites. —Aristotle

Another angle of this unity of opposites is the unity of ascent and descent. Both Heraclitus and Zarathustra have something to say on this particular theme:

“The way up and the way down are one and the same.” — Heraclitus

“Summit and abyss—they are now united in one!” — TSZ 3.1: The Wanderer

This symphony of opposition is the key idea that Zarathustra and Heraclitus have in common. Near the end of the final part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the prophet sings:

“All things are chained and entwined together, all things are in love; …” — TSZ 4.19.10: The Drunken Song

Likewise, Heraclitus says:

“Listening not to me but to the Logos, it is wise to acknowledge that all things are one.”

Heraclitus & Zoroaster

This commonality between Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Heraclitus is startling, but what is also startling is that Heraclitus may have also recognized the common ground between his own thought and the Zarathustra of antiquity, for there are some striking similarities between the two:

- To Heraclitus, the world is a war of opposites; to traditional Zoroastrianism, the world is a war between two opposing forces (Good and Evil).

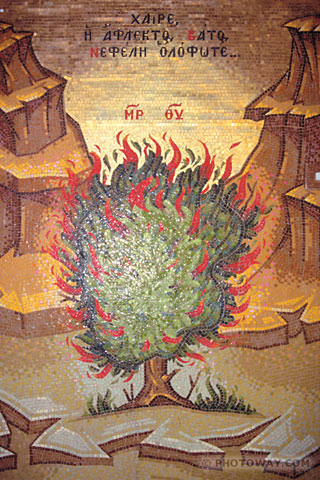

- Heraclitus drew a parallel between his Logos and fire, just as the Zoroastrians’ universal principle of Asha is associated with fire. Heraclitus is thought by many to have taught that the world is made of fire, whereas Zoroastrians are thought to worship fire.

- Heraclitus draws an identity between “the wise” and divinity; the God of Zoroastrianism is named “Lord Wisdom”.

- Heraclitus lived in the Persian Empire, perhaps 1-7 centuries after Zarathustra.

Seeing all this commonality, it is not hard to see a triad formed by Heraclitus and the two Zarathustras. One might venture to assert that both Heraclitus and Nietzsche strove to take the theme of Zarathustra beyond the dogmatism of Zoroastrianism, though, whereas Nietzsche made a point of making references to Zarathustra, Heraclitus appears to have taken the opposite course, perhaps in an effort to avoid being associated with the Persians among his fellow Greeks, or possibly to discourage any suggestion that his “Logos” is in any way a derivative of any doctrine.

Nietzsche could even be seen to have taken that departure into the poetic, musical style of Thus Spoke Zarathustra specifically to serve the theme. In doing so, Nietzsche conceived of a protagonist that is not unlike our image of Heraclitus: something of a hybrid between poet and philosopher; a cryptic, contrary riddler and hermit; an elitest and yet a prophet for universal affirmation. Even Nietzsche’s notion of eternal recurrence, similar to a Stoic doctrine that was likely inspired by Heraclitus’ notion of a cyclic return of things to fire, teaches a somewhat Heraclitean lesson of world-affirmation. There is much in common between Nietzsche and Heraclitus, and much of what they share can be attributed to the legacy of Zoroastrianism, itself a religion of world-affirmation.