The end of August the air

Grew dry and anxious, there were forest-fires inland

And the grass was like gun-powder. … [1]

At this point, our narrative will leap ahead in time to discuss two narrative poems that exhibit the characteristics of a fire narrative. With Cawdor, Jeffers’ use of fire was more restrained than it had been in Tamar and The Women at Point Sur, and Jeffers appeared to cease burning his narrative offerings altogether after The Loving Shepherdess. He returned to fire as a major narrative element in the 1940s, perhaps thinking that he hadn’t been faithful enough to Apology for Bad Dreams when, a decade after Cawdor, horrors began to visit his house.

Mara represents Jeffers’ return to the fire narrative after the passing of a dozen years, published in the 1941 collection Be Angry at the Sun and Other Poems. Though Jeffers’ stated wish for Mara was that it would “bore” its readers, Mara has got to be one of his most compelling narratives: [2]

To-morrow I will take up that heavy poem again

About Ferguson, deceived and jealous man

Who bawled for the truth, the truth, and failed to endure

Its first least gleam. That poem bores me, and I hope will bore

Any sweet soul that reads it, being some ways

My very self but mostly my antipodes;

But having waved the heavy artillery to fire

I must hammer on to an end.

It may be tempting to take this passage as a key to the poem, but one should be cautious about taking the word of a poet, liars that they are. Perhaps one should listen to the poet, but when addressing the soul of a poem one must ultimately trust only the poem itself. One might take the words of one of the angels of Jeffers’ contemporaneous poem, the Bowl of Blood, [3] as a warning:

God’s spokesmen are often liars.

God remains silent.

Rather than this being a story about a “man who bawled for the truth,” Mara seems more about a man who hid from the truth. Yes, he was jealous, but there is so much more to him than that. Was Jeffers being deceptive, or did he change the story after he spoke of being “bored” of it?

The setting is late summer 1939, at the time Nazi Germany invades Poland. The protagonist is Bruce Ferguson, a reflective, conscientious rancher whose young, beautiful wife and brother have an illicit affair under his roof.

Sin, for Ferguson, is of a different sort than that of his wife and brother. His is a sin of awareness and conscientiousness. Whereas they creep around looking to get away with whatever they can, Bruce is too reflective, and so is inclined to let his conscience blame him unfairly. Ferguson’s jealousy is certainly a sin for him as it is born of the sickness of consciousness, but the sin does not end with jealousy. Ferguson would be better off it were, but he has to take things a step further: he heaps shame upon jealousy.

… “Why do I have that slimy dream? … / A man spying on his wife and his brother / Would be too low to live.” … [4]

To reinforce the point that this isn’t all about jealousy, perhaps we should step back and address Ferguson’s less Biblical sins, such as the more practical sins of a rancher. In one early scene, Bruce commits the sin of trying to shortcut through a range-fire. The fire drives his horse mad. The horse injures itself, and Ferguson is forced to euthanize it with his knife and return home on foot through the blaze. Unlike other blazes in Jeffers’ narratives, the beast loses its mind while the man keeps his cool. We see that Bruce Ferguson has a steady mind and a practical awareness of the suffering of other creatures, but the empathy is accompanied by a corrosive sense of shame:

“… The poor colt, / The poor bastard. A what y’ call it, mercy-murder. / I’d nothing but my old knife and the artery / Sprayed like a fire-hose.” He continued, awkward and ashamed: … [5]

Meanwhile, Ferguson’s father, dying slowly of cancer, in steady pain in the attic, is still more consumed by the threat of wildfire than his otherwise intolerable death-pangs. Ferguson’s mother, meanwhile, simmers with a long lifetime of collected resentments. Like her son Bruce she has been faithful, and as with him her good faith has been rewarded with treachery. But the two take different paths—both destructive.

As always with Jeffers but perhaps even more in this case, the beauty of the land—and even the human body—is expressed powerfully.

… Here were cool sand, smooth rock, / Rich moss and the water music; while the ebb-tide ocean / In the autumn heat stank like a beast, and high overhead the flayed gray ridges harsh as flint knives / Flamed in the sun: … [6]

Just as Jeffers describes the beauty of the little coastal canyon, he describes the human beauty of Fawn and her child in terms of inhuman life:

… Fawn knelt in the pool, soaping / The thick fleece of her hair; when she bent to rinse it / The bow of her back and her small buttocks beautifully / Arched from the stream, her mane like rich water-weed / Floated in the green ripple; … while little Joy, fourteen / Months old, played on the bank: … the animal loveliness / Of their naked bodies were bud and flower / O’ the rose-white lily: they were nearly as beautiful as a young panther / With her soft cub: … [7]

But lovely as she is, Fawn’s beauty—even her physical beauty—is marred by her rather human selfishness:

… but Fawn a somewhat degenerate animal / Craving love more than giving it had not been able / To suckle her baby: she had small virgin breasts, / And now recovered from childbirth her smooth belly / Looked virgin too. She stroked herself with her hands / Lovingly, …” [8]

This description is more than a little reminiscent of Tamar in Mal Paso Creek. As with Tamar, this scene of self-adoration presages tragedy.

Fawn watches a distant car fly through a guardrail and tumble down a cliff. She doesn’t run off to tell anyone that she’d seen a great crash, for “there was nothing to do about it at this distance.” This may be an allusion to that remote war, but with regard to the story itself, it is a reflection on the moral near-sightedness of our species; a characteristic Jeffersian reflection on the distortion of perspective at distance. [9]

The treachery of Fawn and Bruce’s brother Allen finally gets to Bruce, and it happens under an aerial bombardment of a summer thunderstorm—“the fire from heaven,” as Jeffers put it 13 years earlier in The Summit Redwood. “A fierce wind through the cracks” breaks into a dance hall, feeding the kerosene flames therein. The musicians catch the spirit of the storm; the music comes to life, the dancing gets wilder, and Bruce Ferguson finally loses his cool. He starts a bloody fist fight with a man who’s been dancing with Fawn. He strikes out at the man because he cannot face the guilt of his wife and brother. As hypothesized in Apology for Bad Dreams, nature eggs man on to tragedy.

The title Mara suggests that Mara is what this poem is about. In the story, Mara is a spirit, not to be conflated with a human ghost, that follows Bruce Ferguson around wherever he goes, though she only becomes visible toward the end of the story, when Ferguson’s passions overcome his wary self-restraint. Her name alludes to Gautama Buddha’s temptress whose name is death. Mara seems to appear at about the time of the murder of Bruce Ferguson’s father, and appears to oversee the death of the protagonist himself, so she does appear to be a spirit of death, but she is not so much a temptress as a sly mocker. When she accuses Ferguson of having been overcome by passion, he scoffs, thinking she speaks of sexual passion, but she is quite right: Bruce, walking alone after attacking a man for dancing with his young wife, is guilty as charged. The tension of the knowledge of his little wife’s affair with his brother had finally spilled over his wall of denial and exploded into misdirected brutality (a Freudian—or Schopenhauerian—touch).

It is the passion that lets Mara into Bruce’s mind. Rather than being a temptress of the passions, this Mara arises to proclaim the triumph of the passions (and a defeat for Buddha nature). Though this Mara differs from the Mara of Buddhism in this detail, she is very much in line with the Buddhist demon, the key difference being that this Mara does not need to tempt anyone to witness the triumph of the passions. She need only observe—and mock.

This might be said to be a poem about two murders (spoiler alert): the murder of a guilty man by his long-suffering and resentful wife, and the murder of their otherwise innocent son by his own conscience, which seems only capable of self-blame. To righteous Bruce Ferguson, the prospect of catching his wife and brother in an act of passion is tantamount only to self-incrimination:

A man spying on his wife and his brother

Would be too low to live.

And thus the story would end.

The final killing is understated, committed as though performing a farm chore. It is a sort of execution, and when it is done, the dead son is conveniently labeled insane and forgotten. In a sense he was indeed insane, maddened as he was by his own conscience. His treacherous wife and brother, finally free of him, enjoy a happy ending.

––––––––––––––––––––

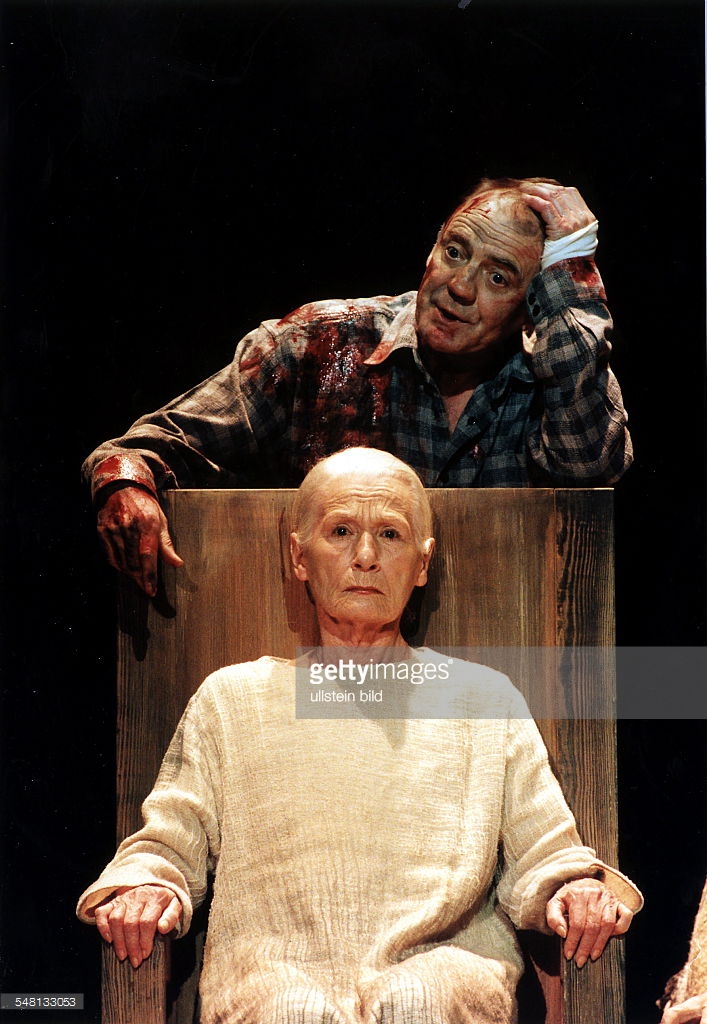

Mara has been refactored into the second act of a stage play, Jeffers Akt I & II (1998), by German playwright Botho Strauss. One production of this play featured Bruno Ganz, an actor that many will remember from the Wim Wenders film, Wings of Desire, in which Ganz played the angel Damiel. Others may have seen Ganz play Adolf Hitler in the 2004 film Downfall. Many others will recognize him for the many YouTube parodies of Hitler rants based on a scene from Downfall. Regretfully, the production of Jeffers Akt I & II in this case was directed to be over-acted and was regarded a bombastic flop rife with unintended humor.

[1] Section IV; CP 3:47

[2] For Una; SP 566–7. Also see Bennett, pg. 168.

[3] CP 3:94. The superhuman character being referenced here is named “First Masker” in the poem.

[4] Section III; CP 3:44–45

[5] Section IV; CP 3:49

[6] Section V; CP 3:50

[7] Section V; CP 3:50

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid, CP 3:51