Man’s character is his fate.

—Heraclitus

“Ethos anthropoi daimon.” What could an old Greek and subject of the Persian Empire have meant by such a declaration? Many modern folk seem inclined to replace the implicit verb “is” with an explicit “determines”. It only makes sense to the modern liberal mind: a man’s character determines his destiny. How else could character relate to the unfolding of events, I suppose that they reason, but that is the rationale of a modern—and somewhat Western—mindset.

As an American, I am accustomed to the mantra of self-determination: “you can be anything you want to be”. I do my best not to repeat it. I certainly have my doubts that a pre-socratic Greek could have been proposing such a doctrine by putting the words ἔθος (disposition, character, custom, habit), ανθρωπος (man, mankind), and δαίμων (divine power, angel, fate, etc.) together.

He might have meant “a man’s custom is his angel,” or maybe “disposition is destiny.” Who can say for sure?

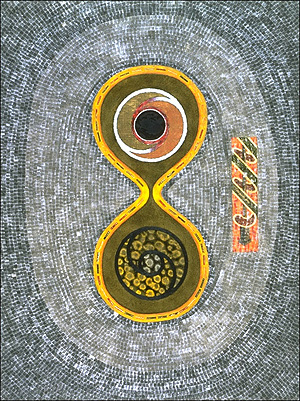

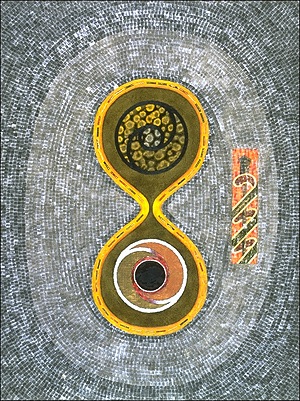

Bernard Maisner, The Way Up Is the Way Down – Heraclitus

We might strive to acquaint ourselves with the man, as obscured as he is by the ravages of time, before attempting to fit his words together. We ought to also consider what his words might have meant to a subject of the Persian Empire who lived before much of what we recognize as western philosophy was even born.

Heraclitus is known most as the philosopher of change. There is little doubt that change was a big part of his philosophy, but there is considerable dispute as to whether change was the centerpiece of his thought. I am inclined to side with those who see Heraclitus as a philosopher of universal unity and interdependence. When he spoke of change, he spoke of it not as arbitrary flux, but as the result of a harmonious dialectic of opposing principles, or forces. Given that, one can hardly see the Heraclitus who summarized his own thought as “all things are one” as a prophet of self-determination or radical individualism, or even of personal determinism.

So what might be a more likely interpretation? I would like to read the aphorism with an eye for irony, which I believe to be warranted given the general pattern of Heraclitean epigrams. If we take the word daimon to mean destiny, we should ask ourselves what Heraclitus might have meant by the word. Would he have meant the final destination of a man, at the moment of death perhaps? The words of Heraclitus give us a strong impression that he did not believe in ultimate destinations. In light of this, I believe it is reasonable to suggest that destiny must be seen as something fulfilled, in an immediate sense. Furthermore, a man who made it clear that he was aware of the external forces that can exert themselves upon a man, could hardly have believed that a man is impervious to external influence. Given these points, it seems to me that Heraclitus must have meant that a man’s character is his destiny, with destiny taken to mean the fulfillment of oneself; that is, not so much that one’s choices determine what one becomes, but rather one’s choices define what one is.

“I am my choices.” — Jean-Paul Sartre

“It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.” — Albus Dumbledore

Does birthplace or name define a person? Hair color, or height? Coordination? Intelligence? Personality? Are these things characteristics, or circumstances? When we look at such so-called characteristics, we soon see them as our personal environment rather than characteristics that we can claim to be our own. Ultimately, the sum of these characteristics is the sum of our environment: existence itself. All things are one.

All that remains for the individual are one’s choices.

One cannot expect to change anything, but one can choose to change anything.

This is a rather stoic definition of personal destiny, but I think a stoic interpretation might be true to Heraclitus, given his evident awareness of the interdependence of things, and stoicism seems appropriate given the homage the stoics often paid to Heraclitus.