This blog got its name “Idol Chatter” for a reason, or even a couple of reasons. First of all, the blogger is a rather militant unitarian (note lowercase ‘u’). Secondly, he tries not to take his own chatter too seriously.

By “unitarian” is here meant anyone who recognizes the tendency of leaders, doctrines, and ideologies to become idols that stand in the way of our search for truth. Idolatry, according to this school of thought, is a mighty sly shape-shifting devil. As a former Unitarian minister once challenged us:

“We boast our emancipation from many superstitions; but if we have broken any idols, it is through a transfer of the idolatry.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Similarly, a Greek philosopher once cautioned:

“It is wise to listen not to me, but to the Logos, …” — Heraclitus

I use the term “unitarian” because this cautious mode of thinking is embodied in the Unitarian tradition, in which some Christians long ago determined that worshiping Jesus is missing the message of Jesus, who did not forbid blasphemy against himself, but rather forbade blasphemy against “the spirit”. It is the spirit of the message that gives life, he said, not the flesh of the messenger; not even the letter of the message.

In this sense, we can see that Jesus, whom some identify with the Logos, was not so different from Nietzsche’s anti-prophet Zarathustra:

“All the names of good and evil are parables: they do not declare, but only hint. Whoever among you seeks knowledge of them is a fool!” — Thus Spoke Zarathustra

The Great Iconoclast

Imagine if you will a medieval man, centuries after Christ, who was familiar with Judaism and Christianity. Imagine that this man was impressed by the Judaic aversion to idolatry, but also recognized Christ as a man—or messenger—of Truth. Imagine that he rejected the Trinity, and the notion that Jesus is God. Imagine that this man became quite well known for his opinion that Jesus is not God, such that we might consider him the first Unitarian. Imagine that he was a man of his time, and realizing the efficacy of power, mustered an army and ordered that army to pursue idolators and smash idols to the ends of the earth.

Let us call this man, for lack of a better name, Muhammad. Maybe this man was so single-minded about smashing idols that he might be called a prophet. Perhaps he was such a dedicated Unitarian that he rejected the very possibility of any religion other than the religion of Unitarianism, going so far as to call himself “the Seal of the Prophets”:

“Muhammad is not the father of any man among you, but he is the Apostle of God, and the seal of the prophets: and God knoweth all things.” Qur’an (Rodwell translation)

Let us further imagine that this man was seen by by his enemies as a militant religious fanatic and his followers as a crusader for his god Allah. Perhaps we can imagine that they had him wrong. Perhaps we can imagine that he was after something more fundamental, and that the rest—his doctrines, methods, and even his personal beliefs—was all circumstantial.

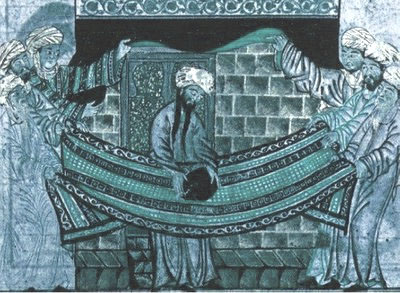

The man in the painting is not going bowling. If we look closely enough, we find that even Muhammad was an idolator; but who isn’t? Shall Muslims be permitted to rise above the man? Not if they continue to idolize him.

It is commonly understood that Islam means “submission”, but submission to what? Submission to Islam? Certainly not. That would be circular, would it not? It has always been understood to mean “submission to God”; but what is God? Is God to be taken as the Islamic image of God, “Allah”, or is God to be taken as that ultimate, unknowable creative essence behind—or within—things? Perhaps the core meaning of Islam is “submission to no idol, however subtle”.

“Seek knowledge even unto China” — Muhammad

If we were to take this as the essence of Islam, could this not be a religion of the future? Could we go so far as to say that Islam is faith in Reason? If this seems like too much of a stretch, can we at least see how Islam might be seen as a medieval attempt to free humanity of idolatry?

Let the true Muslims step forward to smash the idols of Islam.