A couple years ago, my friend Juan and I attempted to follow the route of the old Hockett Trail above Ladybug Camp in Sequoia National Park. We were stopped in our tracks by a wall of brush that has filled in since the maintenance of the trail ceased in 1969. We crawled down some tunnels that wildlife had worn through the chapparral, but the tunnels just kept going and going.

I could well imagine that, had I been a Yokuts or Monache trader a couple centuries ago, I might well have set that thicket on fire, but I wonder whether the Indians of the Sierra had to confront such mature thickets.

In his article Fire in Sierra Nevada Forests: Evaluating the Ecological Impact of Burning by Native Americans, biogeographer Albert J. Parker concludes that Native Americans probably did not have a widespread impact on the ecology of the Sierra Nevada. This goes against a recent trend, largely among social scientists, to propose that aboriginal peoples have actively managed entire landscapes for their economic benefit. The trend appears to be motivated by a desire to represent aboriginal peoples as civilized nations, rather than primitive, passive inhabitants of a natural habitat.

I find the debate interesting. The notion that aboriginal peoples are generally so civilized that they alter entire landscapes does not bring me to any epiphany about the potential of aboriginal peoples for civilization, nor does it improve my opinion of them as naturalists.

No, what strikes me about a mindset that sees all peoples as civilized, and that idealizes the role of aboriginals as stewards of idealized civilizations, is that it appears to see the natural environment as something that ought to be managed. The mindset seems rather biased in favor of civilization itself, and hence, contrary to the idea that people ought to avoid altering their natural environment. The view seems, in a word, anthropocentric.

A sequoia grove — illustration by John Muir.

My respect for aboriginal peoples is generally for their genius for cultural adaptation to a great variety of surroundings; not for altering their surroundings for economic benefit. But, well, they are human after all, so I suppose they’re bound to meddle with things.

More objectively, the basic problem with the landscape-altering aboriginal hypothesis with respect to the Sierra Nevada is that it doesn’t appear to be supported by the facts. There is evidence that indicates that Native Americans did use fire to manage vegetation in the immediate vicinity of villages and summer camps, but the vegetation of the Sierra as a whole appears to have been much more under the influence of climate, topography, geology, and other non-human factors.

The idea that Indians managed the forests of the Sierra Nevada with systematic controlled burns appears to ignore evidence that suggests that the forests of the Sierra Nevada are self-managing:

- The Sierra Nevada is exposed to sufficient lightning, particularly during the dry season, to make naturally-ignited fires frequent enough to avoid excessive build-up of fuel.

- Before fire suppression, fires would often smolder until winter, sometimes sparking other fires.

- Dry conditions in late summer not only dehydrate fuel, but also tend to arrest biological decomposition.

- Preventing the occurrence of hot wildfires might have prevented the establishment of vegetative communities such as Sequoia groves.

- Evidence of Indian burning of lands not adjacent to permanent settlements is scanty to nonexistent.

- Park-like areas of the Sierra so beloved by John Muir, where conceivably man-made, were just as likely a result of the practices of shepherds as that of Indians.

John Muir famously commented on the park-like groves that he witnessed in the Sierra:

The inviting openness of the Sierra woods is one of their most distinguishing characteristics. The trees of all the species stand more or less apart in groves, or in small, irregular groups, enabling one to find a way nearly everywhere, along sunny colonnades and through openings that have a smooth, park-like surface, strewn with brown needles and burs. Now you cross a wild garden, now a meadow, now a ferny, willowy stream; and ever and anon you emerge from all the groves and flowers upon some granite pavement or high, bare ridge commanding superb views above the waving sea of evergreens far and near.

—Muir, The Mountains of California, Chapter 8

Muir was a man of his time. He is known to have been given to exaggeration, and this is no exception. Other accounts that predated Muir clearly indicated that much of the Sierra was covered with vegetative communities other than Muir’s idyllic park lands. I am inclined to believe that Muir’s descriptions of the Sierra often say more about himself; more about his mental landscape than any objective landscape.

It was this same man who likened Yosemite to a cathedral. It sometimes seems he desired that the wilderness should resemble a great stone church encircled by a cemetery of manicured meadows with well-spaced trees for tombstones.

John Muir’s introduction to the Sierra in 1868 was preceded by hordes of sheep, and sheepmen like himself; shepherds who were known to burn out forest floor litter for the benefit of their own activities:

… mill ravages, however, are small as compared with the comprehensive destruction caused by “sheepmen.” Incredible numbers of sheep are driven to the mountain pastures every summer, and their course is ever marked by desolation. Every wild garden is trodden down, the shrubs are stripped of leaves as if devoured by locusts, and the woods are burned. Running fires are set everywhere, with a view to clearing the ground of prostrate trunks, to facilitate the movements of the flocks and improve the pastures. The entire forest belt is thus swept and devastated from one extremity of the range to the other, and, with the exception of the resinous Pinus contorta , Sequoia suffers most of all. Indians burn off the underbrush in certain localities to facilitate deer-hunting, mountaineers and lumbermen carelessly allow their campfires to run; but the fires of the sheepmen, or muttoneers , form more than ninety per cent. of all destructive fires that range the Sierra forests.

—Muir, The Mountains of California, Chapter 8

It appears that Muir was very much in favor of fire suppression!

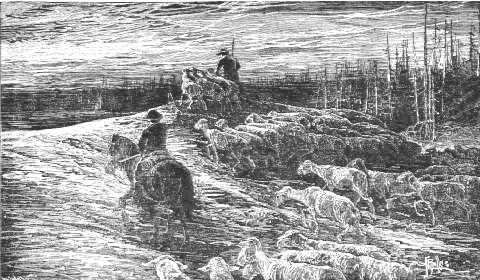

Hoofed locusts — illustration by John Muir.

This reminds me of Muir’s self-serving but eloquent account of his night in a trunk hollow amidst a forest fire near Paradise Ridge in October 1875 (Our National Parks, Chapter IX), and I am inclined to wonder who it was that started that inspiring fire that Muir made so much literary hay of.

When we read about John Muir’s travels through the Sierra, we find, as we would expect, that sheep were quite commonplace. Muir, at last, was not traveling through a virgin wilderness. In many cases, he was probably following livestock trails.

I don’t doubt that open, park-like groves existed in the Sierra before Europeans arrived, and I do value the spacious silence of a Sequoia grove. I also value a path free of obstacles. I’m sure that Indians sometimes burned out brush and forest litter, but I don’t believe that the Indians managed Sierra forest ecology as a whole with systematic controlled burns. Without the fire suppression policies of the 20th Century, there would have been no need for controlled burns. Fires would have found the fuel, and if they didn’t find it immediately, an occasional hot fire fed by “excess” fuel accumulation may have been ecologically beneficial in some respects.

Kilgore (1973) observed that fire is inevitable in the Sierra Nevada, given the climatically dictated imbalance between biomass production (which can be high in most spring and early summer months) and decomposition (which is arrested by dry conditions during summer).

—A. J. Parker, “Fire in Sierra Nevada Forests”

Related entry: The Devil’s Tinderbox

©2008 Dan J. Jensen