We had moved to South Carolina or South Africa four times by the time I turned fifteen. During those four stints, we lived in seven different towns. The principal motive for all this motion was to participate in mass conversion of Blacks to the Bahá’í Faith.

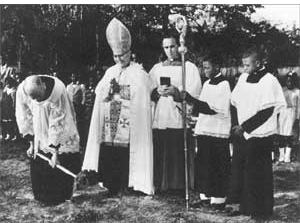

Mass conversion wasn’t just something that we were drawn to because it meant bringing God’s Word to lots of receptive souls. It was, and remains, an essential component of the Bahá’í “entry by troups” prophecy. It is vitally important to the Bahá’í Faith that it expand. For this reason, Bahá’ís have been pushed continuously to relocate to new places so that they might spread the Faith.

It may be that few Bahá’í families were uprooted as completely as ours, and I’m certain that Dad’s wanderlust played a part, but I have no doubt that our displacement was a direct result of directives of the Bahá’í leadership. We were not just spreading the Good Word; we were fulfilling prophecy.

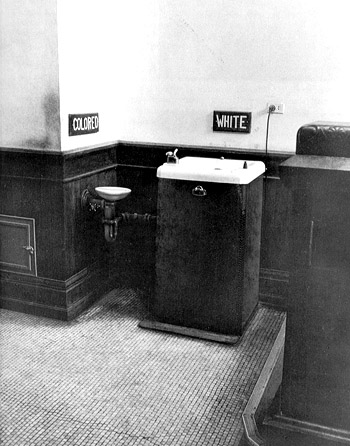

I think, leaving some room for doubt, that we would have stayed put if we could have afforded it. Our problem was that whenever we would go to these spiritual locales, Mom and Dad could never make a decent living. Either there just wasn’t enough of a market, or segregationists would do what they could to discourage Mom and Dad from running an integrated business. In Walterboro, South Carolina, Mom and Dad caught heat for serving both whites and blacks. After Walterboro, they opened a practice in Easley, which enjoys the dubious distinction of being near to the town of Piedmont, made so infamous by the film “Birth of a Nation” as being the fictional cradle of the Klu Klux Klan. Their luck was no better there.

Though I don’t harbor any sympathies for the whole enterprise of saving souls, I respect the effort that Mom and Dad made to live by their principles. I’ve not known many Bahá’ís who were so willing to dedicate their lives to their Cause, and how many Bahá’ís had the courage to take on the twin demons of segregation and apartheid at the business level?

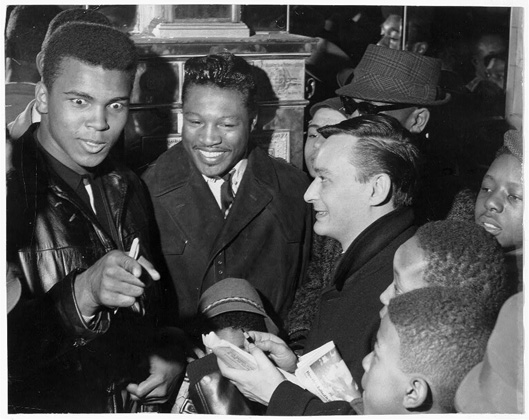

I say courage, but maybe there was some naiveté as well. Still, courage and foolishness are old bedfellows. What I think may have been unfortunate is the price that my oldest sibling paid for our misadventures. Sometimes kids pay a price for their parents’ ambitions, but it’s not as though Mom and Dad abandoned any of us. Speaking for myself, I was too young to notice. Even when I was a teenager in the South—or in South Africa, I was too displaced to care, even when I found myself between the racist overtures of whites and the fists of blacks.