An enumeration of the elements of California might proceed as follows:

- The San Andreas Fault

- The California Current

- The Sierra Nevada

- The Central Valley

- Redwood Forests

The San Andreas Fault

The Pacific and North American Plates, two of the world’s largest, collide from the Gulf of California to Shelter Cove, just south of Cape Mendocino, California. This collision, roughly delineated by the San Andreas Fault, is what put the place we call California on the map.

The California Current

California is probably best known for its climate, a phenomenon which owes no small sum to the fact that California is a collision between continental and oceanic plates, with two particular circumstances:

- The collision has a north-south orientation, with cool ocean currents flowing from the north.

- The collision occurs across a broad spectrum of tropical, subtropical, and temperate latitudes, from 23 to 40 degrees north.

All this adds up to a mild, sunny climate. Add to that an occasional quake to keep everybody on their toes, and you have the California of the Padres.

The Sierra Nevada

Another California was born in 1848, not of sunshine and mild weather, but of greed. That rebirth was initiated and sustained by four gifts of the Sierra Nevada:

- gold

- water

- soil

- beauty and recreation

The massive Sierra Nevada traps large volumes of atmospheric moisture, leaving the lands to the east dry. It being a large mountain block, much of that moisture is stored as snow and ice, meaning that the moisture is released when it is needed most, during the warm, dry springs and summers. As that moisture is released, it carries with it the sediments that become the soils of the great Central Valley.

As lady luck would have it, a smattering of that sediment is gold. It was the glitter of gold in Sierra streams that set the tone for the future of California and America, just as that glitter brought the world to California before her greatest riches were discovered. Beyond the extravagance of gold and the practical benefit of water and soil, we must not forget the beauty and recreational value of Lake Tahoe, Yosemite, the High Sierra, and the Giant Sequoia (more on that to come).

The Central Valley

Without Sierra Nevada sediments, much of the Central Valley might be known today as the Central Sea, like the Sea of Cortes (the Gulf of California) to the south, but the Sierra Nevada does not entirely account for the Central land form of California, be it land or sea, and there are other mountains that feed the Central Valley. The Sacramento River is proof of that. The Sacramento River is fed by the southern end of the Cascade Range on east, and the Trinity Mountains and other ranges on the west.

Redwood Forests

“From the redwood forests to the Gulf Stream waters, this land was made for you and me.” — Woodie Guthrie

Another natural resource that plays a central role in the California myth is the California redwood tree, which lives along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the Pacific Coast, from Big Sur the far southern Oregon.

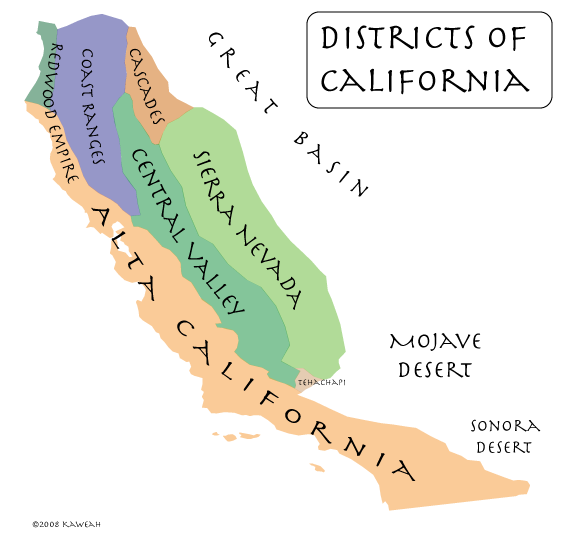

Where is California?

Having taken all these elements of California into account, a natural eastern boundary of California can be seen to proceed along the following features:

- The east coast of Baja California.

- The Colorado River.

- The crest of the Chocolate Mountains (just east of the San Andreas Fault).

- The crest of the Little San Bernardino Mountains.

- The crest of the San Bernardino Mountains.

- The crest of the San Gabriel Mountains.

- The crest of the Tehachapi Mountains.

- The eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada.

- The eastern edge of the Cascade Range. The boundary continues northward here to include the watershed of the Sacramento Valley.

- The crest of the Siskiyou Mountains.

- The northern boundary of the Smith River watershed. This is the approximate northern boundary of the region called “the Redwood Empire”.