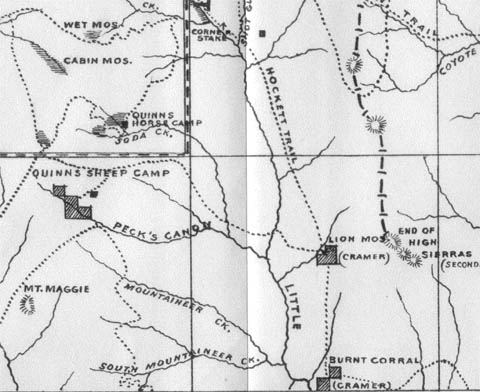

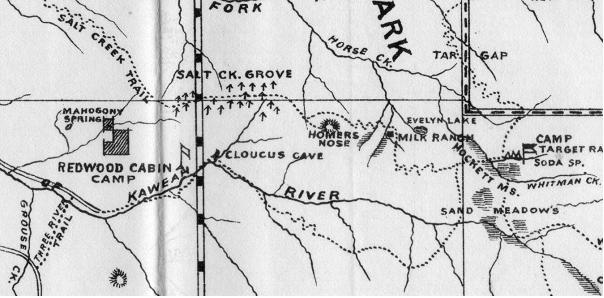

After crossing Hunter Creek, the incline increases as the Hockett Trail leaves the Hockett Plateau for the Western Divide. After ascending 850 feet, the trail reaches a ridgecrest that might deceive a traveler into thinking he’s reached the top, but he has another 300-foot climb ahead. All-in-all, it’s not a difficult ascent to the divide at Wet Meadows Entrance (9824′).

The original boundary of the park actually extended eastward beyond Wet Meadows to a longitude line. Since 1978, the Wet Meadows Entrance has been an entrance into the Golden Trout Wilderness.

The Western Divide is the divide that lies west of the Kern watershed, from Farewell Gap (above Mineral King) to the Greenhorn Mountains. It may be thought of as a branch of the Great Western Divide. It is not, as a whole, given a name on maps, so I take the name from the Western Divide Highway (California State Route 190). It is the first of two divides crossed by the Hockett Trail (the original trail skirted around the Great Western Divide).

On the eastern side of the divide, the trail (31E11) descends toward the Little Kern. The first signs of Wet Meadows bring the trail to a group of large campsites and the roofless remains of a cabin built by the Pitt brothers. At the downstream end of the meadows, there is a rather well-developed camp worth visiting. Be warned, though, that the trail splits at the meadow, and the branch adjacent to the meadow is not maintained.

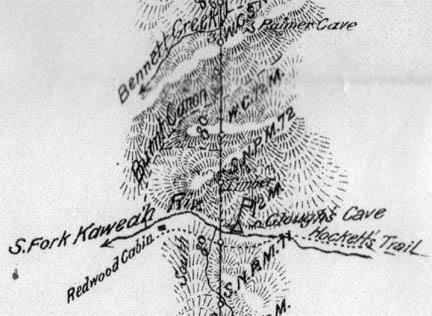

Below the meadow, the trail encounters a trail to Quinn Patrol Cabin (31E13) on the right. From this junction, trail 31E11 continues toward Mineral King, and we descend in an east-southeast direction into the canyon of the Little Kern, taking care to stay south of the hump that rises just south of Wet Meadows Creek. The descent becomes increasingly more steep into the canyon. The last 400 feet are the worst. This route, once-upon-a-time trail 31E12, has not been maintained, or even used for many years, due to the facts that (1) trails in and out of Mineral King provide alternatives that did not exist in the 1860s, and (2) the Forest Service has not maintained trails in the Golden Trout Wilderness since 1995. Thankfully, some routes are maintained by packers, volunteers, and cowboys. There is hope, however, for this abandoned classic: the 2003 Cooney Fire may have cleared some of it for us.

This leg of the Hockett Trail ends at the Little Kern River, where we reach the first trout stream in the native range of the California golden trout. 31E12 and the old Hockett Trail crossed the stream here, as the canyon is more navigable on the east side. The river is relatively calm here, and the canyon bottom is relatively broad. The outlet stream of Wet Meadows, the Little Kern’s first tributary, flows into the river just upstream. See if you can spot the benchmark 7923 on the east side of the river.

See Exploring the Southern Sierra: West Side by Jenkins & Jenkins: Hockett Meadows–Little Kern River Backpack (T93).