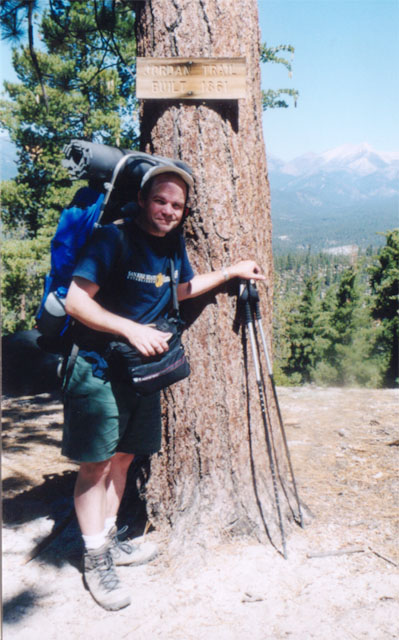

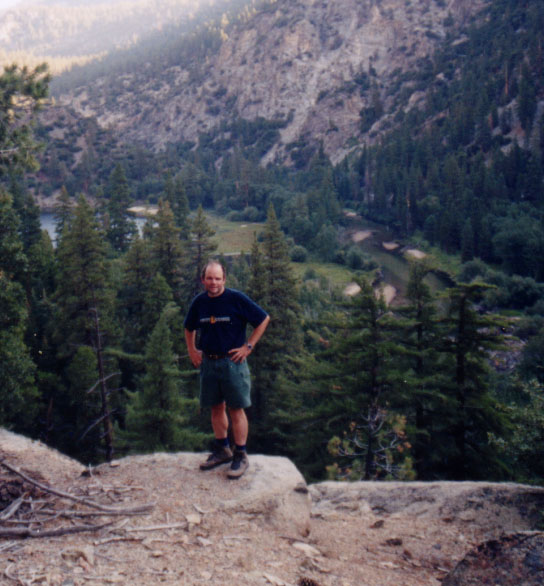

Here, near the headwaters of the Little Kern, is where the Golden Trout leg of the Hockett Trail begins, and the native country of my favorite variety of golden trout.

Ladies and gentlemen, present … fly rods!

… or just sit by the stream and enjoy the show.

The Little Kern descends quickly, then levels out as it flows down a v-shaped canyon toward its confluence with Shotgun and Rifle Creeks. Trail 31E12, which once formed a shortcut between Wet Meadows and Coyote Pass, has been unmaintained since 1995 at least, but the recent Cooney and Tamarack fires may have helped to clear away the accumulated overgrowth (undergrowth to the trees; overgrowth to the trail). About halfway down the canyon, the trail enters another zone of meta-sedimentary schist and marble.

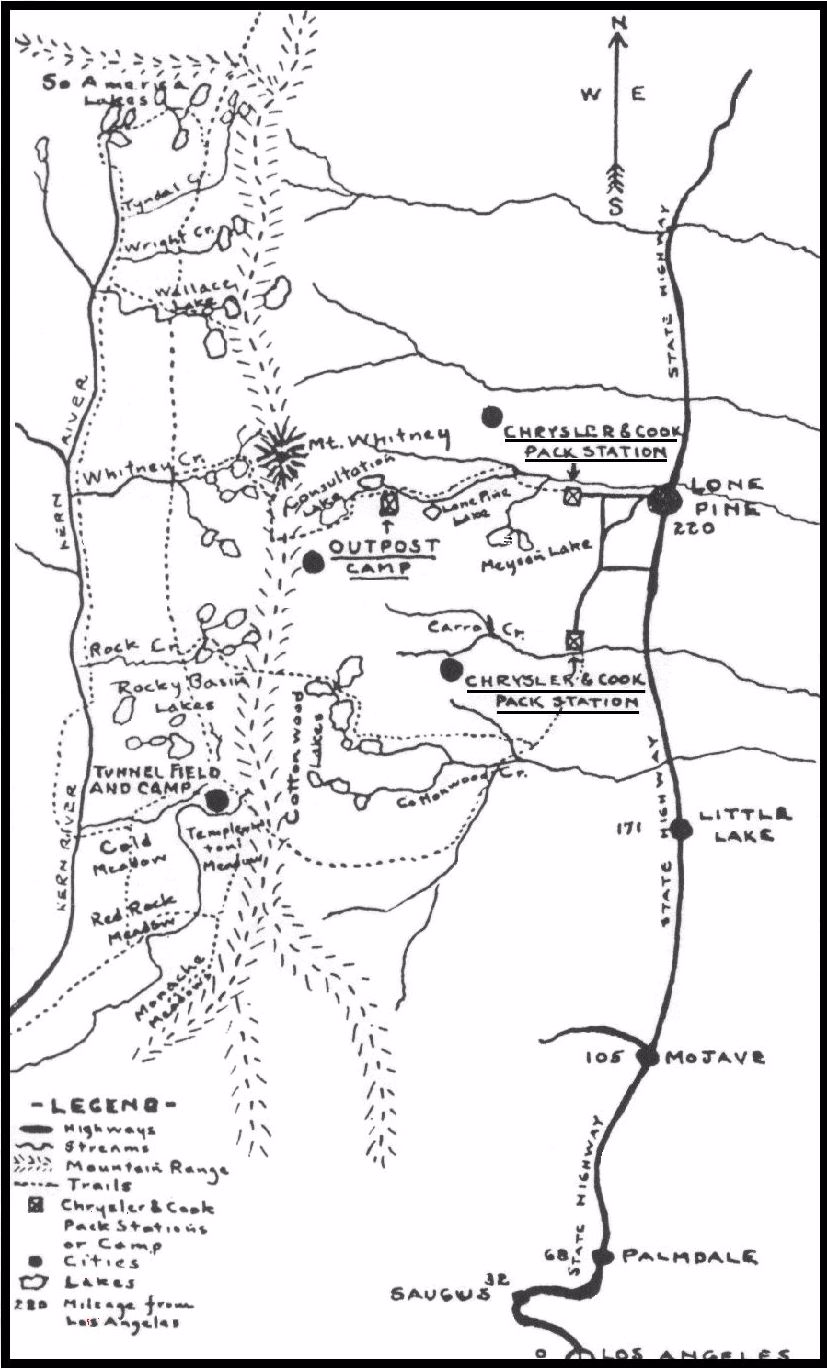

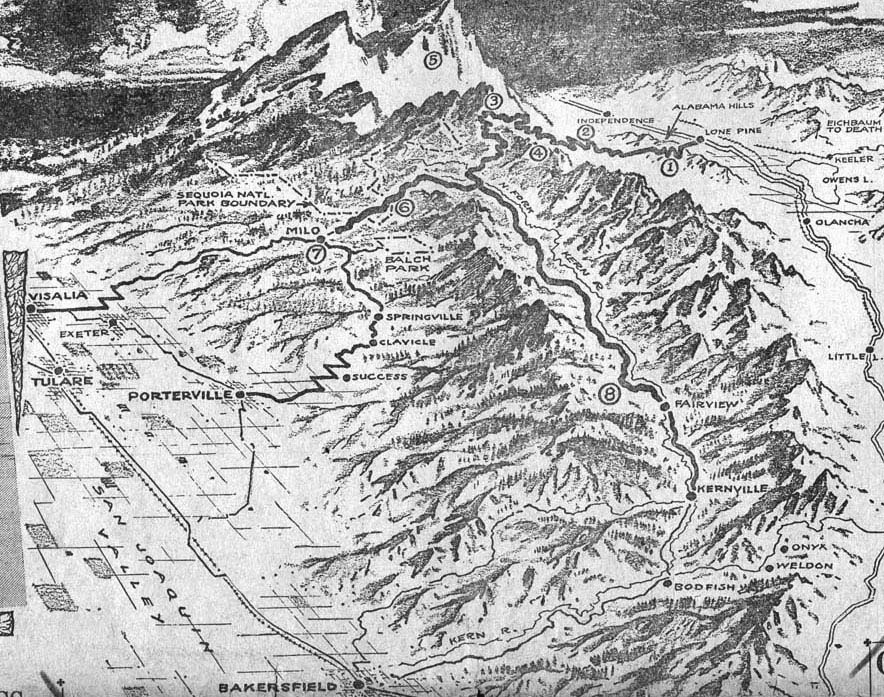

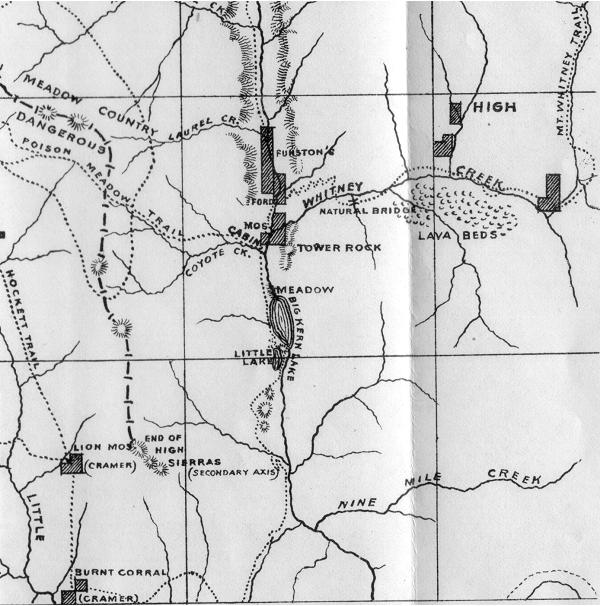

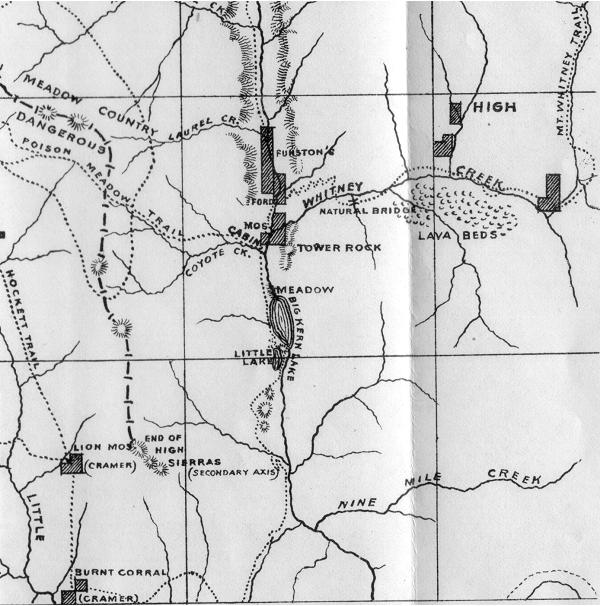

Again, a shortcut to the Kern Canyon follows unmaintained trail 31E12 up over Coyote Pass. Though the original Hockett Trail did not cross the Great Western Divide, and all the accounts that I have read indicated travel around the divide, some early travelers probably did cross the divide at Coyote Pass as a late season alternate. That said, I have seen no early maps that indicate that the Hockett Trail itself crossed the divide; in fact, the only Coyote Pass trail I’ve seen indicated by maps before 1958 was not associated with the Hockett Trail, but proceeded from Mineral King. This is the same general trail that crosses the divide at Coyote Pass today. On an 1896 map of Sequoia National Park, it was labeled the “Poison Meadows Trail”, and “Dangerous”.In Chapter Three of The Challenge of the Big Trees, Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed indicate that the Hockett Trail did indeed cross the Great Western Divide, but the only details they provide on the matter contradict that indication:

“The Hockett Trail began near Tharp’s Ranch on the Kaweah River, ascended the South Fork of the Kaweah to the subalpine plateau now known as Hockett Meadow, then crossed into the Little Kern; it briefly combined with the Jordan Trail only to diverge to the north again and cross the main Kern in the vicinity of Kern Lake.”

The only way the cited passage could be true is if the trail skirted around the Great Western Divide, and met the Jordan (Dennison) Trail at Trout Meadows.

“There are four well beaten trails entering the valley of the little Kern from Tulare Valley and all unite before reaching the Big Kern.” … the roughest, up the South Fork of the Kaweah.” — P. M. Norboe (1903), cited by Floyd L. Otter, Men of the Mammoth Forest, pg 32

W.F. Dean of the Mt. Whitney Club included the following description of the Hockett Trail in an account of a trip that he took in July 1897 from Mineral King to the Chagoopa Plateau:

“We then followed the Hockett trail, via Round Meadow, Lion Meadow, and Burnt Corral Meadow.”

Note that this traveler skirted around the Great Western Divide as late as July, and that he identified the name “Hockett Trail” with that circuitous route.

Still, in spite of so much evidence, local common knowledge has it that the Hockett Trail had a late season branch over the Great Western Divide. Old hearsay dies hard.

From Rifle Creek, unmaintained Forest Service Trail 32E02 follows the river south. The original Hockett Trail ascends southward over a saddle, then descends to join 32E02, and follows that same trail, also unmaintained, to Trout Meadows.

After following the river for about a mile, trail 32E02 veers away from the Little Kern, and does not return to it, but there are places where it is not very far from the river. One such place is where the old Dennison Trail probably merged with the Hockett Trail, at Sagebrush Gulch.

A short hike along the north side of Sagebrush Gulch on unmaintained trail 32E11 takes you down to the Little Kern ford where that mountaineer and man of leisure Dennison may have crossed on his way to the Coso Range. He probably came down off the Western Divide along Mountaineer Creek (wouldn’t that be appropriate?), but we can access this ford more easily via Clicks Creek (also on trail 32E11).

See Exploring the Southern Sierra: West Side by Jenkins & Jenkins: Coyote Lakes Backpack (T58) and Two Rivers Backpack (T59). Also see Hiking California’s Golden Trout Wilderness by Suzanne Swedo: Lion Meadows Loop (11) and Northern Golden Trout Tour (20).