Here’s a tribute to Hockett country that I recently threw together, to the music of U2’s song “Elevation”. Yes, we take the song quite literally, as it serves our present purposes.

Here’s a tribute to Hockett country that I recently threw together, to the music of U2’s song “Elevation”. Yes, we take the song quite literally, as it serves our present purposes.

Note 26 to the Kitáb-i-Aqdas explains the timing of Naw Rúz as follows:

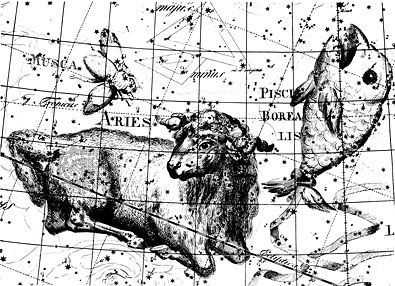

“Naw-Rúz is the first day of the new year. It coincides with the spring equinox in the northern hemisphere, which usually occurs on 21 March. Bahá’u’lláh explains that this feast day is to be celebrated on whatever day the sun passes into the constellation of Aries (i.e. the vernal equinox), even should this occur one minute before sunset.”

Bahá’ís appear to believe that the Sun enters the constellation Aries at some time on or around the Vernal Equinox. This is not so. It was true about 2500 years ago, but not at present. At this time, the Sun enters Aries on April 19, about four weeks after the Equinox. This is because of something called precession.

One might possibly argue that what Bahá’u’llah really meant was the actual equinox (lit. “equal night”), and that the mention of Aries was only meant to refer to the first month (12th) of the astronomical year, but this argument has a leak: the Bahá’í system of watching for the equinox at some time of day is an impossible system, because the equinox cannot be determined empirically until a 12-hour day has passed, and at that point the equinox may need to be retroactively set to the day before (if the day before was closer to 12 hours).

One could conceivably stand at the equator and watch the sun pass overhead, but the sun passes over the equator at a different place each year. Better be on your toes! Of course, thanks to astronomy, one will know where to look. But there’s a catch:

“The Guardian has stated that the implementation, worldwide, of the law concerning the timing of Naw-Rúz will require the choice of a particular spot on earth which will serve as the standard for the fixing of the time of the spring equinox. He also indicated that the choice of this spot has been left to the decision of the Universal House of Justice.” (note 26)

Okay. Nevermind chasing the sun around the equator.

If one is to pick a single observation point, one had better pick a place not frequented by clouds, fog, dust storms, or mountain ranges. Muslims can tell you all about this problem.

There’s one final thing. The suggestion that a single observation point be selected for the determination of the equinox is, alas, manifestly ignorant of the science. The equinox is a global phenomenon. It does happen at a precise time, but it happens to the entire planet, at the moment that the radius vector of the earth’s orbit is at a right angle to the earth’s axis.

“… to be followed by its establishment and recognition as a State religion, which in turn must give way to its assumption of the rights and prerogatives associated with the Bahá’í state, functioning in the plenitude of its powers, a stage which must ultimately culminate in the emergence of the worldwide Bahá’í Commonwealth, animated wholly by the spirit, and operating solely in direct conformity with the laws and principles of Bahá’u’lláh.”—Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice, page 15.

If you’ve read the writings of Shoghi Effendi, you might have gathered that the Baháí Faith will undergo a number of stages before the “World Order of Bahá’u’lláh” is realized. These are those stages as I see them:

More pertinent statements by Shoghi Effendi

This passage clarifies the comprehensive role of the Universal House of Justice in the “future super-state”:

“Not only will the present-day Spiritual Assemblies be styled differently in future, but they will be enabled also to add to their present functions those powers, duties, and prerogatives necessitated by the recognition of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh, not merely as one of the recognized religious systems of the world, but as the State Religion of an independent and Sovereign Power. And as the Bahá’í Faith permeates the masses of the peoples of East and West, and its truth is embraced by the majority of the peoples of a number of the Sovereign States of the world, will the Universal House of Justice attain the plenitude of its power, and exercise, as the supreme organ of the Bahá’í Commonwealth, all the rights, the duties, and responsibilities incumbent upon the world’s future super-state.”—Shoghi Effendi, World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, pages 6-7.

The following passage anticipates the transitional role of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh as a state religion as something similar to the Church established by Constantine:

“This present Crusade, on the threshold of which we now stand, will, moreover, by virtue of the dynamic forces it will release and its wide repercussions over the entire surface of the globe, contribute effectually to the acceleration of yet another process of tremendous significance which will carry the steadily evolving Faith of Bahá’u’lláh through its present stages of obscurity, of repression, of emancipation and of recognition—stages one or another of which Bahá’í national communities in various parts of the world now find themselves in—to the stage of establishment, the stage at which the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh will be recognized by the civil authorities as the state religion, similar to that which Christianity entered in the years following the death of the Emperor Constantine, a stage which must later be followed by the emergence of the Bahá’í state itself, functioning, in all religious and civil matters, in strict accordance with the laws and ordinances of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, the Most Holy, the Mother-Book of the Bahá’í Revelation, a stage which, in the fullness of time, will culminate in the establishment of the World Bahá’í Commonwealth, functioning in the plenitude of its powers, and which will signalize the long-awaited advent of the Christ-promised Kingdom of God on earth—the Kingdom of Bahá’u’lláh …”—Shoghi Effendi, Messages to the Bahá’í World, page 155.

The following passage enumerates the “successive stages” of the evolution of Bahá’í influence to succeed the initial stage of obscurity:

“Indeed, the sequel to this assault may be said to have opened a new chapter in the evolution of the Faith itself, an evolution which, carrying it through the successive stages of repression, of emancipation, of recognition as an independent Revelation, and as a state religion, must lead to the establishment of the Bahá’í state and culminate in the emergence of the Bahá’í World Commonwealth.”—Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By, page 364.

The following passage makes it clear that the Bahá’í Commonwealth is not to be confused with the secular world government that Shoghi Effendi expected to precede the future Bahá’í super-state:

“As regards the International Executive referred to by the Guardian in his “Goal of a New World Order”, it should be noted that this statement refers by no means to the Bahá’í Commonwealth of the future, but simply to that world government which will herald the advent and lead to the final establishment of the World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. The formation of this International Executive, which corresponds to the executive head or board in present-day national governments, is but a step leading to the Bahá’í world government of the future, and hence should not be identified with either the institution of the Guardianship or that of the International House of Justice.”—Shoghi Effendi, Peace Compilation, entry 60.

Bahá’u’lláh’s letter to Mánikchí Ṣáḥib is noteworthy for being one of his few “pure Persian” compositions, but it is not purely pure. In fact, the closing passage, a prayer for forgiveness, is written in Arabic. This would not have made much difference to the addressee, because he was a Parsee, and probably spoke only Hindi and Gujarati. The only difference it might have made is that it may have required an extra translator.

I have no idea whom the prayer asks forgiveness for, if it’s actually asking at all.

Since the prayer is omitted from all English translations of the letter, and because this makes me curious as to what this omission consists of, and because I’m generally curious about everything relating to Zoroastrians, I’ve taken a stab at a rough translation, which is bound to remain an unfinished hack. The prayer begins as follows:

اى ربّ أستغفرک بلسانى و قلبى و نفسى و فؤادى

و روحى و جسدى و جسمى و عظمى و دمى و جلدى ،

و إنّک أنت التّوّاب الرّحيم

O Lord! Thou forgiveth with my tongue, and my heart, and my soul, and my heart, and my spirit, and my body, and my flesh, and my bone, and my [دم], and my skin; verily Thou art the Relenting, the Compassionate.

It’s been over twenty years since I tried to read anything in Arabic. I’ve asked Juan Cole if he ever finished translating the letter, but he’s not got back to me yet. I don’t hold it against him. He’s got bigger fish to fry.

Just in case anyone out there wishes to help me with this, here’s the rest of the prayer. It’s basically a refrain of the form “Thou forgiveth, O my God … Thou forgiveth, O my King … Thou forgiveth, O my Pardoner …,” and ends with two of the 99 names of God, “the Almighty, the All-Knowing.”

و أستغفرک يا إلهى باستغفار

الّذى به تهبّ روائح الغفران على أهل العصيان و به

تُلبس المذنبين من رداء عفوک الجميل . و أستغفرک يا

سلطانى باستغفار الّذى به يظهر سلطان عفوک و عنايتک

و به يستشرق شمس الجود و الافضال على هيکل المذنبين

و أستغفرک يا غافرى و موجدى باستغفار الّذى به يُسر عَنّ

الخاطئون الى شطر عفوک و احسانک و يقومنّ المريدون

لدى باب رحمتک الرّحمن الرّحيم . و أستغفرک يا سيّدى

باستغفار الّذى جعلتَه ناراً لتُحرق کلّ الذّنوب و العصيان

عن کلّ تائب راجع نادم باکى سليم و به يَطهُر اجساد

الممکنات عن کدورات الذّنوب و الآثام و عن کلّ ما

يکرهه نفسُک العزيز العليم

Source: Daryay-e-Danesh, pages 9-10.

| Yeah, that’s right, I consider myself a Mazdean, among other things. I’m sure that there are a lot of Mazdeans who would not consider me a Mazdean, but that doesn’t matter to me. They won’t be around for long anyhow.

Why, you may ask, have I adopted such an ancient, backward, and dying religion? Well it’s not just because I want my corpse to be devoured by birds. Here are the principles of Zoroastrianism as I see it. How does it stack up against your fundamentals? Tell me what you think. |

|

“There is no wisdom save in truth.”—Martin Luther

“Sincerity is impossible unless it pervades the whole being, and the pretense of it saps the very foundation of character.”—James Russell Lowell

Zoroastrianism is a very ancient religion, and its scriptures take us back to a primitive society that hardly seemed to know civilization or large-scale warfare. It is a close cousin of the religion of the Vedas, and so it is like that Olive Tree in the Qur’án which is neither of the East nor the West (yes, Iran is indeed within the native range of the olive). Furthermore, it is the ancient root of my religious heritage, not only in the sense that it has influenced the Bahá’í Faith, but also in its influence of Shí’a Islám, Islám in general, and Judaism and Christianity.

In a sense, I was born a Zoroastrian. I was, in fact, raised to believe that Zoroaster was a perfect incarnation (“manifestation”) of God, which is not at all how I have come to see Zoroaster. I now see him as an inspiring myth for mankind, which is a better thing than any divine prophet idol could ever hope to be.

If that doesn’t convince you to convert, here: Freddie Mercury was a Zoroastrian! (Say no more!)

The Vendidad is the Zoroastrian book of laws that was supposed to have been authored, if not written down, roughly around the time of Christ. The content, though, seems quite ancient. There is very little in the Vendidad that suggests that it was written for a civilized (urban) people, or even a warring people; yet, it is supposed to have been authored after Iran had been civilized for over 600 years. It is because of the ancient character of the content that I’m inclined to believe it retained much from an older, primitive tradition.

Reading the Vendidad, one might nearly guess that the supposed author was aware of little more than his own tribe. There’s nothing in the Vendidad about national or intertribal government, kings, or even warfare, though the existence of unbelievers is acknowledged. There are several passages that indicate some discrimination against unbelievers; for instance, murdering an unbeliever does not appear to be regarded as a crime (as in Judaism, perhaps to distinguish murder from warfare), and it also seems that an unbeliever could be absolved of some crimes by converting to Mazdaism.

There are also indications that Mazdean law does not apply to unbelievers, and that would seem to be corroborated by history. The Parthian Empire was evidently a relatively tolerant, loosely-organized empire, and though the Parthians’ Sasanian (Sassanid) successors were quite strict with regard to treason, heresy, and apostasy, they appear to have sometimes permitted Jews and Christians to live somewhat autonomously under their reign. It is thought that the Sasanians were the first rulers to apply what became known as the “millet” system, wherein each recognized religious group would enforce its own laws internally.

“… under the early Sasanians much of the groundwork for the future was established. For example the authority over political and economic affairs of the heads of various religious minorities, famous as the millet system of the much later Ottoman Empire, seems to have been organized by the early Sasanians, as well as the tax system applied to minorities.”

The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods

Edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater

The Cambridge History of Iran

Page 132

‘It was likewise under Sassanid rule that the first agreement which can properly be called by the name of “millet” was concluded.’

Religion and Nationality

Werner J. Cahnman

“In 410 AD, during the rule of Yazgard I (399-420), Christians were recognized as a millet, or separate religious community, and were protected as such within the organization of the Sassanid Empire. The Sassanid law recognized that the Head of the Christian millet was responsible for upholding discipline within the millet and that the state gave formal backing and recognition to the Head.”

The Christians of Lebanon

Political Rights in Islamic Law

By David D. Grafton

Page 20

The millet system of Yazdagird I, the enlightened rule of other Sassanid kings like Hormizd IV, and the open rule of the Parthians were, in a sense, continuations of a more ancient tradition of interfaith tolerance; established a millennium earlier by Cyrus the Great.

Unfortunately, this and other gestures of Royal toleration were more than equaled by waves of persecution, usually driven by the Zoroastrian priesthood. This is no surprise, for the people most invested in the status quo (the priesthood and aristocracy), as well as the people that must have truly believed the doctrines of traditional Zoroastrianism would have been in natural opposition to religions like Christianity, Mazdakism, and Manichaenism. Irreconcilable beliefs about eternal salvation and damnation are bound to fall into conflict before long.

Still, the situation was not simple. Persecution against Manichaenism, for instance, only flared up after 30 years of royal support had allowed the young faith to flourish. Persecution against Christians, for their part, was often a reaction against Christian expansion efforts and refusal to respect the gods of other peoples.

The question I am attempting to find an answer for is: did Zoroastrianism help or hurt the situation? I am inclined to believe the latter. The dominant traditionalism was too strong to permit toleration for long, in spite of more enlightened aspects of the faith. It was typically the kings who sought tolerance, perhaps realizing a modest tolerance to be in the best interests of the Empire.

The September 13 episode of the Philosopher’s Zone podcast really struck a chord with me. I spent most of the episode mumbling non-verbal cues of non-committal acquiescence, but by the end I was slapping the steering wheel, saying, “that’s fucking beautiful” with tears welling up in my eyes. Your mileage, of course, may vary.

The key, to violate the plot line and jump to the climax, is to recognize the sympathetic and value-conscious aspects of love. Adam Smith came close when he recognized the sympathetic nature of human intelligence, and some Stoics seem to have believed in our natural capacity to appropriate others into our sense of self-consciousness (oikeiosis), but neither party, so far as I know, combined the notions of sympathy and value-consciousness as does Australian philosopher Jeanette Kennett:

What I saw so vividly in the most general sense was my son as a valuer.

Her trembling voice, no doubt, may have influenced my reaction, but this thinking has a deep appeal to me. It is not enough to sympathize with the joy and pain of others (please read Smith before you correct me with the word “empathize”). That is fine, but I believe the word “love” means something more, and the idea that we directly experience—or “see vividly”—the subjective value-consciousness of others is about as close as I’ve heard an idea get.

Thank you for listening, that was very brave of you. People have to learn that underlying business, the message of everything is love. Which is why society sticks together. You and I have love. —Jonathan, in Tell me I’m Here by Anne Deveson

If I’m selling Adam Smith or the Stoics short here, please let me have it. I would be happy to give them their due.

Because I believe love to be an innate inclination, I cannot use this line of reasoning to endorse Christian love, because Christian love is founded on a narrative of divine love. The dominant idea taught by the Christ-myth is that God loves us, therefore we ought to love one another. This sounds nice, but I believe that it undermines one aspect of love that I value most: its innate character. I would rather associate with the Stoics, who likely wielded a great influence upon Christianity, and came very close to speaking what I feel to be the truth.

Still, it seems to me that all classical western models miss an critical ingredient: value. Perhaps they left it out because they took value for granted. Perhaps it went without saying, but I believe that, in this age, it needs to be said. Plato came close in his near-deification of Beauty, but he didn’t develop that theme enough to convince me that he acknowledged the fundamental importance of value. I know that sounds rather circular: of course value is important! But I don’t mean to say that our sense of value is tied to what we find important; rather, I believe that our very existence is value-laden.

In looking for a classical symbol of this point of view, if not a philosopher or a kindred spirit, I cannot think of a better example than Zoroaster (Zarathushtra) for his essential intuition of a value-laden world, though the insights of the Stoic theory of oikeiosis and Smith’s theory of moral sentiments are crucial. … And let’s not forget Kennett!

PS: At the risk of sounding elitist, I’m not sure that I would have ever appreciated such discussions on love had I not become a parent.

The Bahá’í religion, though Islamic in its fundamentals, retains a remarkable wealth of Zoroastrian residue from its Iranian heritage.

The Most Great Peace

In spite of all the prophecies of doom that I had to endure as a young Bahá’í, I remember having a vision of a more distant future utopia; a clean, civilized world civilization that would balance urban and rural economies, and accomplish great scientific and technological feats. This is what Bahá’ís call the Most Great Peace. Though I now find it unrealistic, I still look back on that naive vision with sentimental sighs of what might have been if reality hadn’t broken into my childhood and robbed my world of its innocence.

Yet there are many Bahá’ís who still look forward to the Most Great Peace.

It was years after I abandoned that vision that I encountered the ancient vision in whose womb the Most Great Peace appears to have been conceived. I discovered that the ancient Zoroastrians also had such a utopian vision of a renewed, purified world. Note that they weren’t looking forward to the end of the world, but rather its reform and renewal. This vision permeates both Bahá’í and Zoroastrian world views.

Progressive Revelation

It’s not just a utopian view of the future that these oldest and newest of Iranian religions have in common, but their views on the purpose and history of religion are also quite similar:

Be it known that, the reason for mankind becoming doers of work of a superior kind is religion; and it is owing to it only that there is a living in prosperity through the Creator. It is always necessary to send it (religion) from time to time to keep men back from being mixed up with sin and to regenerate them. … All the reformers of mankind (i.e. prophets) are considered as connected with its (religion’s) design;… —Dénkard 3.35

Thoughts, Words, & Deeds

The phrase “doers of work” in the above passage is reminiscent of the great Zoroastrian mantra “good thoughts good words good deeds.” Does this not recall one of characteristic themes of the Bahá’í Faith, as a religion of deeds that recognizes the influential nature of words?

Glory, Light, & Fire

As I’ve discussed before, the closely related themes of fire, light, and glory are also held in common between these two faiths. Some of this commonality can be tracked through Iranian religious themes of illumination and glory from Zoroastrianism through Shí’a Islám to the Bahá’í Faith.

The “New” Calendar

Then there’s the Bahá’í calendar, which is based on the old Iranian solar calendar—from name days, feasts, an end-of-year adjustment, to No Rooz itself, rather than the lunar Islamic calendar, except that the Bahá’í calendar replaces the natural 12:1 lunar:solar cycle ratio with 19:1, and inserts a month of fasting (in Islamic fashion).

Fire Temples and Sunrise Temples

Even the Bahá’í “mashriqu’l-adhkar”, a term that carries an intimation of fire in its meaning “dawning place of remembrance” seems to hearken back to the old Persian fire temples than the Islamic mosques that were also inspired thereby:

… The fire-temples of the world stand as eloquent testimony to this truth. In their time they summoned, with burning zeal, all the inhabitants of the earth to Him Who is the Spirit of purity. —Bahá’u’lláh, in a letter to Mírzá Abu’l-Fadl

Etc.

Some related entries:

Today’s relatively inspiring slice is from the pages of “The Dispensation of Bahá’u’lláh”, by the fifth leader of the Bábahá’í revelation, Shoghi Effendi:

… the fundamental principle which constitutes the bedrock of Bahá’í belief, the principle that religious truth is not absolute but relative, that Divine Revelation is orderly, continuous and progressive and not spasmodic or final.

This is probably the most foundational statement on the doctrine of “progressive revelation” in the Bahá’í writings. It might be argued that Shoghi Effendi’s approach might reach a little too far by establishing relativism as the foundation of his religion. It might be a great argument, come to think of it, for no revelation at all. Why not have God come to each person on that person’s terms, so that person can best learn what he needs to learn from God? God doubtless has the time to make house calls, so why not go the distance and do the job right? Indeed, if God wishes to avoid spasmodic revelation, it seems to me that personal revelation might be the way to go.

The Bahá’í idea of relativism in revelation is depends on the premise that men only progress as a society more than they do as individuals. According to Bahá’í thinking, I have more in common with my bushman contemporaries than I do with a Roman or a Greek from two millennia back. My spiritual maturity is strictly defined by the millennium in which I reside, regardless of my education or culture.

The doctrine of progressive revelation, quite contrary to the doom-laden Islamic doctrine of a final, corrective revelation, is actually quite reminiscent of an old Iranian idea about the renewal of the world.

Be it known that, the reason for mankind becoming doers of work of a superior kind is religion; and it is owing to it only that there is a living in prosperity through the Creator. It is always necessary to send it (religion) from time to time to keep men back from being mixed up with sin and to regenerate them. … All the reformers of mankind (i.e. prophets) are considered as connected with its (religion’s) design;… —Dénkard 3.35

… or perhaps an Indo-Iranian idea, as this does resemble the Indian idea of divine guidance somewhat.

Unlike the Bahá’í vision, this ancient Iranian vision does foresee a time when revelation will cease, because it will not be needed any longer.

there will be no necessity for sending religion, through a prophet, for the (benefit of) Creatures of the world who will be in existence after him (Soshyant)…. —Dénkard 3.35

Though the vision does not involve an idea of continuing incremental progress, it does involve the ideas of periodic rejuvenation, and eventually, a complete renewal of the world.

Today’s slice of enlightenment is our first contribution from the pen of `Abdu’l-Bahá’, the son of the second, greater Bahá’í Manifestation:

If you seek immunity from the sway of the forces of the contingent world, hang the ‘Most Great Name’ in your dwelling, wear the ring of the ‘Most Great Name’ on your finger, place the picture of `Abdu’l-Bahá in your home and always recite the prayers that I have written. Then you will behold the marvelous effect they produce. Those so-called forces will prove but illusions and will be wiped out and exterminated.

—Lights of Guidance, page 520*

This explains a lot. It helps us to better understand why Bahá’ís are so fond of talismans, rote recitation, and graven images of their most charismatic and photogenic leader.

* Word has it that this passage is from a letter addressed to Ms. Emma Ort, cited in a UHJ letter and in the original Persian in Safínih-i ‘Irfán volume 7, page 22.