Continued. When we left off, Zarathushtra was explaining his reasoning for enforcing morality with Heaven and Hell.

Idol Chatter: Even if the punishment fits the crime and Hell has an end, don’t you think this kind of compensation for good behavior undermines our esteem of virtue itself?

Zarathushtra: There is certainly that danger, but at least virtue has entered the conversation. The hope is that once men believe that they have the ability to choose the Good, then they are on the road to the realization that the Good lies within them.

IC: Fair enough; but still, shouldn’t virtue be considered its own reward?

Z: Ultimately, the word “reward” ought to be dropped. Virtue needs no reward.

IC: Great, but what do you have to offer the person who already recognizes this, who is not motivated by greed?

Z: Nothing! They have no need for my preaching!

IC: But why not try to instill natural good will in people?

Z: Why instill what is natural? My task is only to lead the horse to water. The horse will enjoy the water enough without my goading. To speak of individual virtue at all is to miss the point. Ultimately, virtue is not an individual trait; it is a shared experience.

IC: It is said that you rejected the capricious gods of the Indo-Aryan pantheon and replaced them with a moral God, or was it a moral pantheon?

Z: One god; two gods; three gods; one god with three personas: what’s the difference? So long as the gods serve the Good, it is good religion. Most of the old gods were gods of might, and worship of might, whether of one almighty God or of a pantheon of celestial powers is worship that is misdirected.

IC: How so?

Z: Might is essentially amoral. To whatever extent divine might is revered, divinity becomes that much more a tyranny. God must be a servant to the Good.

IC: And what is “the Good?” Who is to say?

Z: I see the Good as Plato did; the ultimate universal. I see Good as the unification of ethics and metaphysics, the two branches of philosophy. Wisdom—sophia—is intimately tied to the Good.

IC: Lord Wisdom: Ahura Mazda.

Z: Precisely. It is as the poet said: “truth is beauty and beauty is truth,” only I think the poet did not understand that aesthetics is a subspecies of ethics. You and I both know the Good, but we have no blueprint for it. There are no names for it. We only know that it is good. We may often mistake it for evil, but it cannot be anything but good.

IC: It has long been reported, since Plutarch, Herodotus, and perhaps farther back, that the distinctive doctrine of your religion is cosmic dualism, the idea that the world is a battlefield between the forces of Good and Evil, but some modern reformers contest this.

Z: Yes. Some modern Zoroastrians are ashamed of the idea, but I suspect that is because they, like many of their forebears, read the idea too literally.

IC: Let’s look at the idea more closely, then. Would you contend that nothing in existence is morally indifferent?

Z: That is one way to put it, yes.

IC: But surely you would not attribute evil intent to, say, a landslide.

Z: I don’t see it as a matter of intention. The morality of a landslide is not intrinsic; it is a matter of the suffering, or even aesthetic joy, that it brings about. If there were no joy or suffering, there would be no good or evil; and the converse applies as well.

IC: Would you say that good and evil are subjective?

Z: Not strictly. Much of good and evil is a common experience, though we experience joy and suffering as individuals. We have no reason to believe that joy and suffering are not in part objective, or even fundamentally so.

IC: But do you think that existence is fundamentally moral?

Z: I suppose my best answer for that is that all our perceptions are fundamentally moral, and all that we perceive is all that matters. A more contemporary, existentialist way to say this is that all phenomena are value-laden.

IC: I’ve long wondered: is it true that you were killed in a siege of Bactra?

Z: That’s my story, and I’m sticking with it!

IC: If that is the case, how can I be talking to you here and now?

Z: Well I was reborn, of course.

IC: You don’t mean that your soul was reincarnated.

Z: Of course not. Just another avatar, nothing more.

IC: Of course. Say, could you do me one final favor?

Z: I don’t see why not.

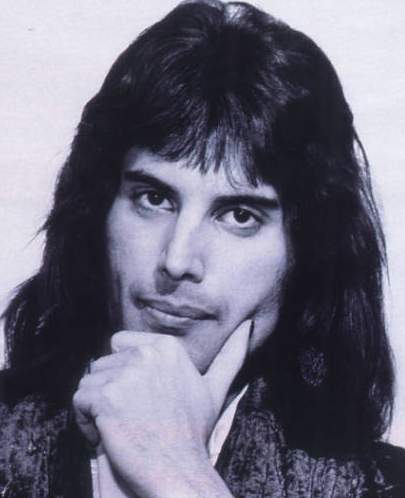

IC: Could you sing the opening verse of Fat Bottomed Girls? You know: “I was just a skinny lad …”

Z: Hah! If I could sing, do you think I’d have time for you? [winks]