I often remark, in contrast to one persistent cliché, that

I am religious but not spiritual.

By this, I don’t mean that I’m a heartless churchgoer. Who do I mean?

First, let’s look at the word “spiritual.” What I mean by “not spiritual” is that, so far as I can tell, the world doesn’t appear to be populated by spirits. I don’t see ghosts or gods. So far as I’m concerned, all I see is nature, and I don’t see any good reason to posit any existence beyond nature. To me, “spiritual” is a word that stands in direct opposition to “natural.”

But I am not simply non-spiritual. Even more than I am not spiritual, I am religious.

What do I mean by this? I mean that I see sacredness in the world. It would not be enough for me to describe my view as naturalistic, because that term is too often conflated with objectivistic indifference. I cannot describe myself as indifferent. I don’t even believe that indifference exists, for in every moment of my life I have cared about whatever I was experiencing, though it be only subtly. I care about everything I see, touch, hear, smell, taste, or imagine. Never have I experienced anything valueless, whether its value be good or bad. Never have I been utterly indifferent.

It’s simple: we care. We must see value in our existence, and we must behave accordingly. When I say, “we must,” I mean that it cannot be avoided. It is the nature of our existence. If there is any Great Power in our lives, it is this: caring.

This doesn’t mean that we’re always good or that we’re always right. It merely means that we are always engaged in a moral struggle, an existential sort of holy war—an existential jihad. Just as we may disapprove of others, we may disapprove of ourselves. We disapprove because we care.

It’s a simple religion, but it seems very hard for most people to understand. I do, however, know of a few who seem to have understood it.

- The German existentialist Heidegger saw our “being in the world” as neither material nor spiritual, but a state of “caring.”

- The American naturalist Henry David Thoreau saw “our whole lives” as “startlingly moral.” Thoreau’s personal philosophy of being has been described as an “ethical metaphysics.”

- Zarathushtra, that ancient Iranian existentialist and revolutionary, recognized for his moral metaphysics by Nietzsche himself, spoke of two qualities in existence—the good and the bad—the two fundamental “qualia” of human perception.

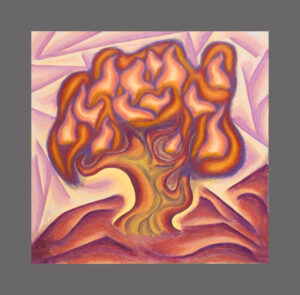

- The philosopher Heraclitus, a Greek subject of the Persian Empire, seems to have seen the world in a similar light. He saw all things in a kind of constant struggle, saying that the world is not composed of earth, water, or air, but poetically, of fire. “War is the father of all,” he said, but by “war,” he clearly didn’t mean violence between nations; rather, he meant that there is struggle in everything, and this struggle need not be seen Newtonian terms (in terms of opposite physical forces). It may be seen in a phenomenological sense, as ethical, even esthetic.

- Alfred North Whitehead, an English mathematician given to lengthy philosophical exposition, also appeared to appreciate this principle when he said, somewhat succinctly, “value is coextensive with reality.”

Having established that we care, or at least that I have a very strong conviction that we care, one might ask, “what ought we to do then?” My best answer to that question is that, paradoxically, we ought to do what we must do.

All ya can do is do what you must

You do what you must do and ya do it well

I’ll do it for you, honey baby

Can’t you tell?

—Bob Dylan

We must struggle for what we find worthy of struggle. As we are thinking beings, this struggle will inevitably be guided by thought (however imperfect), just as thought must necessarily be guided by that existential state of caring.

Given this position, it would not be suitable for me to suggest any particular politics, though I personally prefer particular values, strategies, policies, and so forth. When speaking from a perspective of faith, it is better to let the caring mind determine what is wise, rather than dictate wisdom to it, as it were, in a box.

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.” —Plutarch

As I have implied above, the struggle is esthetic as much as it is ethical. A good thing, whether it be an idea or an action, is beautiful by merit of its virtue. Likewise, a beautiful impression is also a good impression. Religion and art are one. Ethics and esthetics are two sides of one coin—that precious coin of our value-centered existence.

Since Zarathushtra is generally given credit for the insight behind my religion, I call my religion Zoroastrianism. You may call it what you like.