Read more about this in Men Without Fear, available at Amazon.

Harry J. Sutcliffe was born in Brooklyn, New York on 10 August 1925. He was delivered premature and lost his sight soon thereafter to an incubator mishap.

The “age of radio” was a special time to be a blind kid. Amateur radio was also a fascination of many blind hobbyists, one of whom was young Harry Sutcliffe. Anthony Mannino describes Sutcliffe’s career as a “ham” operator in his April 1963 Blind American article:

At the age of thirteen the young student became interested in amateur radio, and by the time he was sixteen was a confirmed “ham” operator. He did a great deal of reading of technical material on the subject and studied under the expert teaching of Bob Gunderson, well-known teacher of the blind. During World War II there were fifteen or twenty amateur radio operators at the school, who worked for the Radio Intelligence Division of the Federal Communications Commission, engaged in recording propaganda broadcasts. Young Sutcliffe also worked for the War Emergencies Radio Services of the Office of Civilian Defense of New York, covering telephone failures resulting from attack or other emergencies. For his participation in this important work he was awarded a citation by the late Fiorello LaGuardia, then Mayor of New York City.[1]

One of Harry’s schoolmates, Joseph Giovanelli, who was often bullied at the Institute, remembered Harry thus in his 2010 autobiography:

Harry Sutcliffe, … like me, was mistreated quite often. He handled it better than I could. … Ham radio changed him from an introverted boy who lacked confidence into an out-going and well-adjusted guy.

… Harry reached a point in his studies where he learned enough to become a licensed amateur radio operator. He patiently explained some basic principles by which radios worked. Sometimes when I was home on a weekend I would hear Harry talking to other amateur radio operators (hams). That was really exciting.[2]

Unlike my father and so many other boys at the Institute, Harry was no wrestler, though he seemed to keep himself in outstanding physical condition. He was not an extraordinary high school student. He was nearly 19 when he graduated from the Institute. Though Harry and Dad did not appear to know each other very well, they would turn out to have one thing in common: a love for scripture.

Throughout his life, Harry would be a student of language. Though not always the consummate student he was a heady young man, and like many of the blind, he developed a love for the written and spoken word. One of the Institute’s teachers reported on Harry in the following limerick:

He is an indefatigable student of Latin

At home in the judge’s velvets and satins

Fond of rational spiels

And radio squeals,

And frequently is late for his matins.[3]

College

After Harry graduated in 1944, the New York Institute’s Pelham Progress reported:

Harry Sutcliffe, who has always intended entering the ministry, has at last realized his ambition and he is now at Wittenberg College in Ohio preparing for the Lutheran church.

Harry graduated magna cum laude in four years, a member of a number of honor societies: Delta Phi Alpha, Phi Mu Alpha Symphonia, Phi Eta Sigma, national Blue Key honorary, Pi Sigma Alpha and Phi Sigma Iota.[4]

Harry attended the Lutheran seminary at Mount Airy in Philadelphia, and earned a bachelor of divinity there in 1951. He specialized in exegetical theology, the study of sacred scriptures with Hebrew and Aramaic.[5] He graduated second in his class.

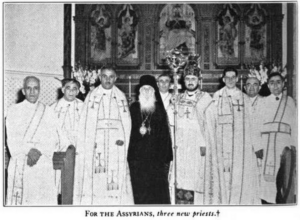

The Priesthood

Harry didn’t remain a Lutheran. He was ordained an Episcopal priest in the year after he graduated from Mt. Airy. At first, the Episcopal Church rejected him because of his blindness, but Harry found a way. The Assyrian rite contains a special form of ordination for the blind (priests were sometimes blinded in Ottoman Turkey), so Harry ‘studied for the priesthood at the Aramaic Church of the East church “St. Thomas Church” on Cabot Street in New Britain,’ Connecticut. He was ordained in the Assyrian “Church of the East,” the first non-Assyrian to be ordained in the American chapter of the Church of the East. His first position was as an assistant in the Chicago Parish of Mar Sargis. His assignment was to “render into the Braille alphabet all the services of the Church translated into English from the Aramaic, and will conduct them according to the traditional forms, but in English.”

The newly ordained “Father Sutcliffe” is third from the right in the following photograph:

Now an ordained priest, Harry Sutcliffe was able to transfer to the Episcopal Church.

Interfaith Service

In 1956, the American Church Union of the Episcopal Church started a new fellowship for the blind and appointed Father Sutcliffe its chaplain.[6]

In 1958, Father Sutcliffe began work as an instructor at the Jewish Braille Institute.[7] He was appointed director of the Episcopal Guild for the Blind when that body was founded in 1959, and he would remain in that position for at least 28 years.[8]

Bishop Bert Schlossberg, once a reader for Father Sutcliffe, remembers him thus:[9]

Harry was a Lutheran, … who was sick (though a Gentile) of the anti-semitism in his church, so he became an Episcopalian, and an Anglo-Catholic one at that, learned Yiddish, he already knew German having broken one of the German codes for the War Department, and became a featured speaker at both B’nai B’rith, (they loved him), and the Hebrew Christian Alliance (we loved him too). As an Episcopal priest, Harry became the one man Episcopal Guild for the Blind, sending out and marking Braille Bible studies. ….

Harry’s interfaith work, including teaching Hebrew and Hebrew Braille to sightless Jews, earned him the appreciation of organizations such as the Hebrew Christian Alliance and B’nai B’rith International (an prominent Jewish community service organization), whose lodge in Lowell, Massachusetts awarded Father Sutcliffe its “Man of the Year Award” on Feb. 24, 1959. The award was presented by Frank Goldman, the Honorary International President of B’nai B’rith.[10]

Sutcliffe also delivered talks before the Anti-Defamation League.

Schlossberg fondly reminisces about an incident that occurred at about the time Harry Sutcliffe won that award:[11]

One day, I was about 20 years old,[12] then, Harry wanted me to take him to Greenwich Village in Manhattan, N.Y. to the Club Sabra, an Israeli, mainly Hebrew language, night club, in order to hear a famous, exotic Yemenite Israeli singer, Shoshana Damari. She would be found many times on the front lines with Israeli soldiers, much like Bob Hope with American soldiers. That’s all Harry told me. Harry was short of comment, straight to the point, truly humble of spirit, and trusted God. And he just loved the music of Shoshana Damari. …

… We arrived at the Club Sabra, which was almost completely darkened, except for an open area in the center, from which, subdued lighting was filtering amongst the many people milling about, talking, many in Hebrew, drinking, laughing. I made my way toward the light, leading Harry holding on to my arm (this is always the way to lead a blind person – do not grab his arm, let him hold your arm). I was trying to look for a table where we could sit, and be comfortable waiting for the show. Finally we made our way toward the dim light flickering through moving bodies, until I had to lead Harry, dressed as always, in his black clergy suit and white priest’s collar, very clumsily, up onto an elevation (“Sorry, Harry!”) near the light, where I thought there would be some tables.

Instead, where I had led Harry (my poor vision), was onto the stage, where he and I found ourselves standing in the center, and now right in the center of the spot light—and right next to us was Shoshana Damari! Shoshana turned around, looked at us with delight, and with microphone in hand, turned to the audience, hushed them, and excitedly said with a great deal of happiness, “I want to introduce you all to my good friend, Father Harry Sutcliffe!” to a good, loud, round of applause by an Israeli audience who had absolutely no idea who in the world was Fr. Harry Sutcliffe, except that he was Shoshana’s friend. But Shoshana knew! And, of course, so did God. That one was from God, straight for Harry, for him alone, with Shoshana and me for witnesses – but I tell it to you now.

In summer 1962, Father Sutcliffe went on a nationwide lecture tour. The impression he left upon people was later remarked upon by Anthony Mannino:

Even in the limited time of a most enjoyable afternoon visit at the Brotherhood office, we were deeply impressed by the magnetism of his personality, fine stature and obvious physical fitness.[13]

Mannino observed how hard a worker Father Sutcliffe was known to be:

From his own office he serves as an instructor for the Hadley School for the Blind of Winnetka, Illinois, supervising the correspondence courses in Greek and Hebrew. In connection with the Hadley program, he is at present rewriting the school’s Bible survey course, with additional chapters on later developments such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and other archeological discoveries.[14]

Father Sutcliffe was a tireless advocate of what he called “the organized blind movement.” Mannino points to a distinction between Sutcliffe’s efforts to bring dignity to the blind and efforts of others to employ the blind in “sheltered” sweat shops:

In summarizing the reasons for his own efforts on behalf of the blind, he maintains that if “work for the blind”—a wonderful phrase which sometimes covers a multitude of sins—is truly sincere in its wish to see blind persons integrated into the community, then the agencies and groups who represent work for the blind will not fight the organized blind movement.[15]

Father Sutcliffe appeared to have obtained a PhD at some point between 1963 and 1980.[16] In 1987 he was appointed onto the National Council on the Handicapped (by President Reagan). So far as I can guess he is still around at 91 years, living in his hometown of Brooklyn.

© 2016 Kaweah

[1] Mannino, Anthony G. “Father Sutcliffe: A Brother to Others.” The Blind American. April 1963

[2] Giovanelli, Joe. Let There Be Light: The Inspirational Achievements of a Man Born Blind. 2010. Pp. 33–34, 84

[3] Hoard, Seth. Pelham Progress, 15 March 1944

[4] Mannino, Anthony G. “Father Sutcliffe: A Brother to Others.” The Blind American. April 1963

[5] ibid.

[6] “Program for the Blind: New ACU Project.” The Living Church, vol. 132, 18 March 1956.

[7] Jewish Post, 26 Feb 1960

[8] “Help for the Sight and Hearing Impaired.” Ministry: International Journal for Pastors, July 1981. Father Sutcliffe appears to have remained director of the guild when he was appointed to the National Council on the Handicapped in 1987.

[9] Facebook. Bishop Bert Schlossberg, 28 August 2016

[10] St. Petersburg Times, 1961

[11] Facebook. Bishop Bert Schlossberg, Syro-Chaldean Church of North America, 28 August 2016

[12] 1958/59.

[13] Mannino, April 1963

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid.

[16] Simons, D.B. “Christian Record Extends Loving Care.” The Mid-America Adventist Reaper, 12 June 1980, page 2. Also see “Help for the Sight and Hearing Impaired.” Ministry: International Journal for Pastors, July 1981.