Read more about this in Men Without Fear, available at Amazon.

John Jensen wasn’t the only gifted wrestler to come out of the NY Institute. Three other blind wrestlers from the school won Metropolitan AAU titles in the years from 1942 to 1948, and a couple nearly took national titles in 1944 and 1946, Their names were Jacob Twersky, Anthony Mattei, Gene Manfrini, and Fred Tarrant.

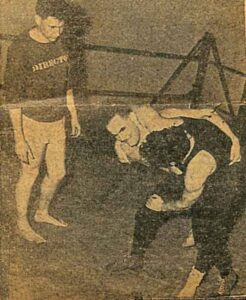

In 1944, the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind featured three wrestlers from ages 15 to 17 who would either win metropolitan titles or nearly win national titles. John Jensen, then 19, was their captain.

I call these athletes “batmen” because they were blind (some more blind than others) and so fought their battles in the darkness.